Blogs | JPL | July 14, 2008

Here We Are ... at Saturn

Here we are, four years after the Cassini spacecraft entered orbit around Saturn. We're about to begin the extended mission, termed the Cassini Equinox Mission. Cassini has been a scientifically remarkable mission and a fantastic return on the investment. If you are reading this blog, then you might already know about Cassini's discoveries at Enceladus, Titan, the other icy moons, the rings, the magnetosphere and Saturn itself. But if you're new to following this mission, you can catch up on those discoveries by reading about them here: http://saturn.jpl.nasa.gov/news/features/feature20080627.cfm.

This great science is accomplished by an international team of scientists and engineers. I am thrilled to be able to carry the scientific reins for Cassini as its incoming project scientist. The project scientist is essentially the mission's chief scientist, who watches out for the overall scientific integrity of the mission.

My own background is in the geology of icy moons of the outer solar system. Though the planets have always enthralled me, I trace this specific icy interest back to a course I took as an undergraduate at Cornell University in about 1984, taught by Carl Sagan and his post-doctoral research associate Reid Thompson, entitled "Ices and Oceans in the Outer Solar System." The course included discussion of Jupiter's moon Europa, which it was thought might have a globe-girdling ocean beneath its icy surface -- an idea that would be further tested by the Galileo spacecraft when it arrived at Jupiter a decade later. We also learned about Saturn's haze-shrouded moon Titan, which might just have seas of organic rain and liquids on its surface -- but we wouldn't know for certain until the Cassini spacecraft arrived at Saturn two decades later. Who could possibly wait so long? And who would have thought that once we all did, both of these seemingly far-fetched ideas would turn out to be correct? (If only Carl and Reid could be here today to know it.)

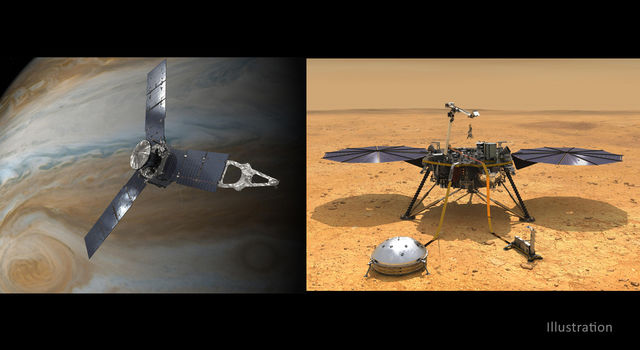

Two years ago I came to JPL with the goal of getting the next flagship mission to the outer solar system off the ground. It takes a great deal of time and energy to make such a mission a reality. They are relatively expensive and take a long time from concept to completion. But just as others before me -- such as Galileo Project Scientist Torrence Johnson and Cassini Project Scientist Dennis Matson -- have worked to send those missions into space, I would help create the next mission, potentially to orbit Jupiter's moon Europa. Currently I serve as JPL's study scientist for the Europa Orbiter mission concept. This mission concept is in friendly competition with a mission that would orbit Titan. I hope that somehow, in time, we can make both of these spectacular mission concepts come to fruition.

Entering into the wonderland that is Cassini, my eyes are wide open to the science and engineering behind the curtain, while wary of its history and complexity. My operating philosophy is to always be true to the science. With good planning and good fortune, Cassini will keep going down the road for many years to come, following up on its prime mission discoveries and in making new ones that we can't dream of yet.

Stay tuned for more to come. It'll be a great ride!

TAGS:CASSINI, SATURN, SOLAR SYSTEM, SPACECRAFT, MISSION