Blogs | JPL | June 17, 2010

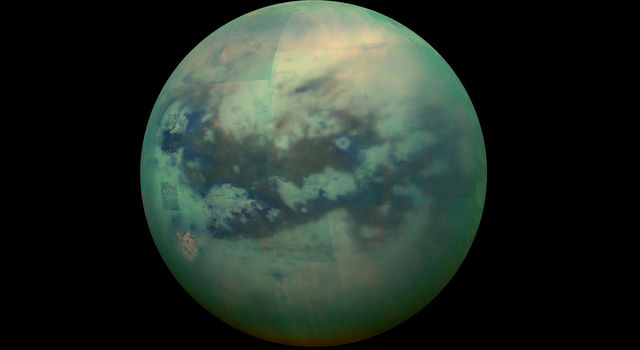

Cassini to Swing Low Into Titan's Atmosphere

This weekend, Cassini will embark on an exciting mission: trying to establish if Titan, Saturn's largest moon, possesses a magnetic field of its own. This is important for understanding the moon's interior and geochemical evolution.

For Titan scientists, this is one of the most anticipated flybys of the whole mission. We want to get as close to the surface with our magnetometer as possible for a one-of-a-kind scan of the moon. Magnetometer team scientists (including me) have a reputation for pushing the lower limits. In a world of infinite possibilities, we would have liked many flybys at 800 kilometers. But we went back and forth a lot with the engineers, who have to ensure the safety of the spacecraft and fuel reserves. We agreed on one flyby at 880 kilometers (547 miles) and both sides were happy.

Flying at this low altitude will mark the first time Cassini will be below the moon's ionosphere, a shell of electrons and other charged particles that make up the upper part of the atmosphere. As a result, the spacecraft will find itself in a region almost entirely shielded from Saturn's magnetic field and will be able to detect any magnetic signature originating from within Titan.

Titan orbits within the confines of the magnetic bubble around Saturn and is permanently exposed to the planet's magnetic disturbances. Previous measurements by NASA's Voyager spacecraft and Cassini at altitudes above 950 kilometers (590 miles) have shown that Titan does not possess an appreciable magnetic field capable of counterbalancing Saturn's. However, this does not imply that Titan's field is zero. We'd like to know what the internal field might be, no matter how small.

The internal structure of Titan can be probed remotely from its gravitational field or its magnetic properties. Planets with a magnetic field -- like Titan's parent Saturn or our Earth -- are believed to generate their global-scale magnetic fields from a mechanism called a dynamo. Dynamo magnetic fields are generated from currents in a molten core where charge-conducting materials such as metals are flowing around each other and also undergoing other stresses because of the planet's rotation.

We might not find a magnetic field at all. A positive detection of an internal magnetic field from Titan could imply one of the following:

a) Titan's interior still bears enough energy to sustain a dynamo.

b) Titan's interior is "cold" (and therefore has no dynamo), but its crust is magnetized in a similar way as Mars' crust. If this is the case, we should find out how this magnetization took place.

c) Something under the surface of Titan got charged temporarily by Saturn's magnetic field before this Cassini flyby. While I said earlier that the ionosphere shields the Titan atmosphere from Saturn's magnetic bubble, the ionosphere is only an active shield when the moon is exposed to sunlight. During part of its orbit around the planet, Titan is in the dark and magnetic field lines from Saturn can reach the Titan surface. A temporary magnetic field can be created if there is a conducting layer, like an ocean, on or below the moon's crust.

Once Cassini leaves Titan, the spacecraft will perform a series of rolls to fine-calibrate its magnetometer in order to assess T70 measurements with the highest precision. We're looking forward to poring through the data coming down, especially after all the negotiations we had to make for them!

TAGS:SOLAR SYSTEM, SATURN, CASSINI, FLYBY, TITAN