Blogs | Dawn Journal | January 30, 2010

January 2010

Dear Plausible Dawniabilities,

Patiently and reliably continuing with its interplanetary voyage, Dawn is now flying in a new configuration and, from the perspective of those readers who may be on Earth, in a new direction.

The spacecraft still spends most of its time gradually changing its orbit around the Sun by thrusting with its ion propulsion system. The probe is outfitted with 3 ion thrusters, assigned the heartwarming names thruster #1, thruster #2, and thruster #3. (The nomenclature and locations of the units were divulged in a log shortly after launch, before such information could be distorted and used unethically by others.) The ship only uses 1 thruster at a time. All 3 were tested during the 80-day initial checkout phase of the mission, and when the interplanetary cruise phase commenced in December 2007, it was thruster #3 that was responsible for pushing the spacecraft away from the Sun. It performed flawlessly, but engineers plan to share the workload among the thrusters over the course of the 8-year mission, so thruster #1 was called into action in June 2008. By that time, stalwart #3 had been operated in space for 158 days. (For those readers who have just returned from an enjoyable excursion back to that log, the apparent discrepancy between the 158 days of operating time given here and the 149 days presented there is not an error. The smaller value is the operating time in the interplanetary cruise phase. Thruster #3 had accumulated about 9 days of operation during the initial checkout phase.)

Thruster #1 was in service until this month. Although it remains in excellent condition, engineers transmitted instructions in December for the spacecraft to reconfigure for use of a different thruster after its weekly communications session on January 4. By that time, #1 had thrust for almost 318 days. With its famously efficient use of xenon propellant, all that maneuvering consumed only 84.6 kilograms (187 pounds), yet it imparted 2.2 kilometers/second (4900 miles/hour) to the spacecraft.

Now it is #2’s turn. It had barely more than 1 day of total running time in space prior to this month, having been used only for some tests in November 2007 and April and May 2009 . Now 2010 will be its year to shine (with a lovely blue-green glow). In addition, as we will see in the next log, for the entirety of the mission, thruster #2 will have the distinction of providing the greatest acceleration to the spacecraft of any of the thrusters.

There is much more to the ion propulsion system than the thrusters. As explained in more detail in an earlier log, the system also includes 2 computer controllers and 2 units that draw as much as 2500 watts from Dawn’s solar arrays and converts the power to the currents and voltages the thrusters need. Controller #1 and power unit #1 are used for both thruster #1 and #3, so those electrical devices have already worked extensively during the mission, although most of their operation still lies ahead. For now, though, controller #2 and power unit #2 are in charge.

Although thruster #2 and its associated components have spent most of their time in space unpowered, they all are now performing just as smoothly as the other ion propulsion system elements did when they were in use.

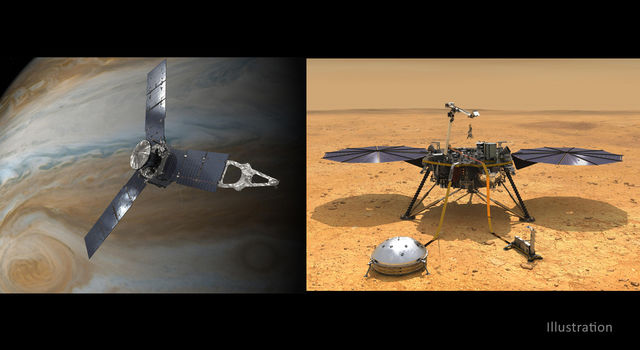

Most of the artistic depictions of the spacecraft in flight happen to show it using thruster #2, the one nearest the main antenna. So the next time you see such an image, probably even at the top of this very page, you might consider that it is very much the way the spacecraft would look right now if you could see it.

Of course, Dawn is much too far from Earth to be seen by human eyes, even aided by the most powerful telescopes. But it has recently come nearer to the planet than it had been for nearly 2 years. As we have discussed in many logs (see, for example, November 2008), Earth and Dawn move independently through the solar system. Just as the hands of a clock sometimes move closer together and sometimes farther apart, Dawn and Earth sometimes approach each other and sometimes separate.

Some readers may not be at all surprised that even as the probe is receding from the Sun well over 2 years after launch, blazing a trail through the asteroid belt, constantly changing its own orbit (unlike most spacecraft, which coast most of the time, just as planets do), it is no farther from Earth than it was just 5 months after launch. They are excused from reading the material below. Others, however, may find this discussion helpful in thinking more about why this occurs. It is not important for the mission, but it may be satisfying for those who wish to direct a metaphorical gaze to the distant craft.

Unlike clock hands, Dawn does not travel in a circular path. Following the initial push away from Earth by the Delta rocket that carried it from Cape Canaveral into space, its orbit around the Sun was elliptical (see the second row of the table here). Its path has changed a great deal since then, principally because of the extensive thrusting (but also because of the gravitational boost from Mars).

Although elliptical orbits distort the picture a little, the essentials of the clock analogy are valid, so let’s imagine this alignment by considering the same clock we have used twice before, most recently last month (For readers who now have more clocks than room to display them, we promise that this will be that last reference to a clock from the Dawn gift shop, at least until your clocks’ warranties have expired.) With the Sun at the center, Earth is at the tip of the shorter hand and Dawn at the tip of the longer one. On January 25, the star, planet, and spacecraft were aligned as closely as the hands of the clock would be at 6:32:16.

When positioned that way, the Sun and Dawn were nearly in opposite directions from Earth’s vantage point. Suppose you were on Earth on that date and wanted to look in the direction of the spacecraft. You would have put the Sun at your back and Dawn would have been less than 6 degrees from your line of sight, equivalent to being in the center of a (different) clock, having the 12 at your back, and instead of looking at the 6, shifting your gaze almost to the next tic mark. (The positions constantly change, and by the middle of February, you would need to readjust your gaze to the 7, still keeping the Sun at the 12.)

Although the alignment is the result of the motion of both Earth and the spacecraft, from the terrestrial perspective, with our deceptive sense of cosmic immobility, it seemed that Dawn had been moving closer to us. Now it seems to be moving away.

Dawn reached its greatest distance from Earth so far in the mission on November 10, 2008. [Note: We had decided that it was unnecessary to include a link to that paragraph, thanks to our encouragement therein for readers to memorize it. According to our new consultants, Prescient Telepaths ‘R Us, you are the sole reader who did not commit it to memory. Therefore, in our goal to make every customer happy, we are pleased to include the link specifically for you. Enjoy!] At that time, it was 2.57 astronomical units (AU) from Earth. Since then, while its orbit has carried it closer to the Sun and then farther again, the distance to Earth has been declining the entire time. The spacecraft and its planet of origin finally moved to their closest point on January 18, when their travels brought them to 0.80 AU from each other. (It occurred at about 2:00 am PST, so if you sleep deeply, you may have missed it.) The minimum distance did not occur at exactly the same time as the nearly linear arrangement because the orbits are not as simple as the circular motion of the clock hands.

The last time they were this close was on March 11, 2008. They will never be so near each other again. Earth follows the same orbit around the Sun year after year, but with Dawn constantly changing its trajectory, pushing deeper into the solar system, the next time it and Earth are aligned on the same side of the Sun (in August 2011), the explorer will be much farther away. Indeed, if all goes according to plan, it will be in orbit around Vesta by then, beginning to reap the rewards for its long expedition through the cold depths of space, as it explores a distant and alien world that waits silently for its first visitor.

Dawn is 0.82 AU (123 million kilometers or 76 million miles) from Earth, or 345 times as far as the moon and 0.83 times as far as the Sun. Radio signals, traveling at the universal limit of the speed of light, take 14 minutes to make the round trip.

Dr. Marc D. Rayman

6:00 pm PST January 30, 2010

TAGS:DAWN, VESTA, CERES, DWARF PLANET, MISSION, SPACECRAFT