Blogs | Southern Exposure | November 12, 2015

Introduction to the Ice

Welcome! This blog is intended to provide a behind-the-scenes look at life and work as a researcher in Antarctica. My trip begins tonight and I intend to update this blog with all of my interesting experiences as I travel to the "ice" as well as a discussion of the science we intend to do and the technology we have engineered to do it!

Traveling to Antarctica is what I imagine the experience of visiting a foreign planet would be like. With no plant life and a very arid climate, the continent feels surreal and unlike anything I have ever sensed elsewhere on Earth. I look forward to sharing my journey as we launch the Stratospheric Terahertz Observatory II (STO-2) from Willy Field!

Please feel free to contact me through my Science and Technology Personnel website with any questions and I will try my best to address them in future blog posts. As an added incentive to encourage questions from my readers, I will write postcards to the first 20 individuals and all K-12 classrooms who email me a question with their name and address.

My first trip to the ice was for STO's maiden voyage in the Antarctic spring and summer of 2011-2012. After my first trip, I learned that people have a lot of questions and misconceptions about the continent, so I want to start by addressing some of the most commonly asked questions.

First of all, geographically Antarctica refers to the southern-most continent on the planet. It is spring right now in the Southern Hemisphere and at McMurdo Station the sun is out 24 hours a day. The last sunset was Oct. 23, 2015, and the next sunset will be February 21, 2016. At McMurdo, we stay on New Zealand time (PST plus 21 hours) since it is the closest country to us.

The Arctic refers to the northern polar region. The Antarctic refers to the southern polar region.

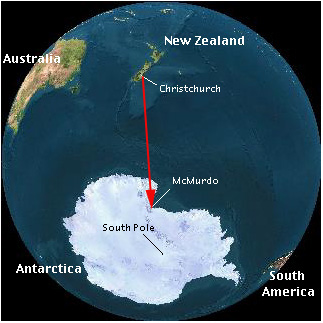

Antarctica does not belong to any one country. Instead, it is governed by a treaty among 53 countries that preserves the continent for scientific exploration and bans any military activity. Currently, 30 countries operate bases for research. The United States has three main bases and two smaller outposts. I will be stationed at McMurdo, which has its closest approach from New Zealand and is by far the largest base on the continent with more than 100 buildings and about 1,000 people during the summer season.

In order to get to McMurdo, everyone flies commercially to Christchurch, New Zealand. (Another frequent misconception is whether I fly through Chile to get to Antarctica. There is a in fact a U.S. station on that side of the continent called Palmer Station, but it is not where I will be going.) The day after we arrive in Christchurch, also referred to as CHC (pronounced: cheech) because of the airport code, we are issued Extreme Cold Weather (ECW) gear from the Clothing Distribution Center (CDC). The CDC is where we pick up the big red jackets for which the the U.S. Antarctic Program (USAP) is famous. I loved my "big red" last time and returning it upon redeployment was such sweet sorrow. (No, we do not get to keep any of this stuff.) I am looking forward to our re-acquaintance!

Ice flights usually occur the day after visiting the CDC. If I am lucky, when I show up for my flight, it will be a C-17 plane. If not, I will fly an LC-130. What is the difference? A C-17 is basically a first-class cargo plane. It has jet engines and can reach Antarctica in around five hours. The flight crew installs real seats, and it has a bathroom, too! Although I have never been unlucky enough to fly a LC-130, my understanding is that plane is more like the Ryan Air of cargo planes -- you just sort of strap in wherever and hope for the best. If one needs to use the restroom while in flight, there is a privacy screen with a bucket. Since these planes do not have jet engines, the trip takes a whopping eight or nine hours! Similarly, weather conditions in Antarctica are unpredictable. It is possible that the flight will get canceled after all the passengers get to at the airport. Even worse is the "boomerang," in which we fly all the way to the continent, cannot land, and have to return to CHC. That means 10, or even 16 hours in flight and then you have to try again at the next available opportunity. Is anyone still interested in stowing away in my luggage as science cargo?

Upon my arrival in McMurdo, I will participate in a scientific balloon mission to launch a telescope into the stratosphere (the second major layer of Earth's atmosphere) to study how stars are born. This is the poor man's version of going to space. We will commute daily from McMurdo to an airfield located about eight miles away on the Ross Ice Shelf. We go to Antarctica for the polar vortex that sets up around the summer solstice. (There is also one in the winter, but flights are only conducted in the summer.) Each rotation around the continent lasts about 14 days, and if we launch early enough, we may continue for another rotation. The wind patterns have set up as early as December 5, but usually are not ready until after December 15. Last time I was there, the vortex was not ready until December 25, so unfortunately I do not yet know our launch date. Dear readers will have to stay tuned!

So how long will I stay down there? It really depends on when we are able to launch. Last time, because of the unusually late set up of the polar vortex and strong ground winds, STO did not launch until January 15. More factors, such as available flights back and weather conditions for planes to take off, play a role. In short, I am preparing to stay a while.

Questions? Topics related to Antarctica or STO-2 you would like to see addressed? Please email me!

TAGS:STO-2, ANTARCTICA, MCMURDO, ASTRONOMY, ASTROPHYSICS, BALLOONING