Dawn Journal | June 29, 2015

Bright Spots Aren't the Only Mysteries on Dwarf Planet Ceres

Dear Evidawnce-Based Readers,

Dawn is continuing to unveil a Ceres of mysteries at the first dwarf planet discovered. The spacecraft has been extremely productive, returning a wealth of photographs and other scientific measurements to reveal the nature of this exotic alien world of rock and ice. First glimpsed more than 200 years ago as a dot of light among the stars, Ceres is the only dwarf planet between the sun and Neptune.

Dawn has been orbiting Ceres every 3.1 days at an altitude of 2,700 miles (4,400 kilometers). As described last month, the probe aimed its powerful sensors at the strange landscape throughout each long, slow passage over the side of Ceres facing the sun. Meanwhile, Ceres turned on its axis every nine hours, presenting itself to the ambassador from Earth. On the half of each revolution when Dawn was above ground that was cloaked in the darkness of night, it pointed its main antenna to that planet far, far away and radioed its precious findings to eager Earthlings (although the results will be available for others throughout the cosmos as well). Dawn began this second mapping campaign (also known as "survey orbit") on June 5, and tomorrow it will complete its eighth and final revolution.

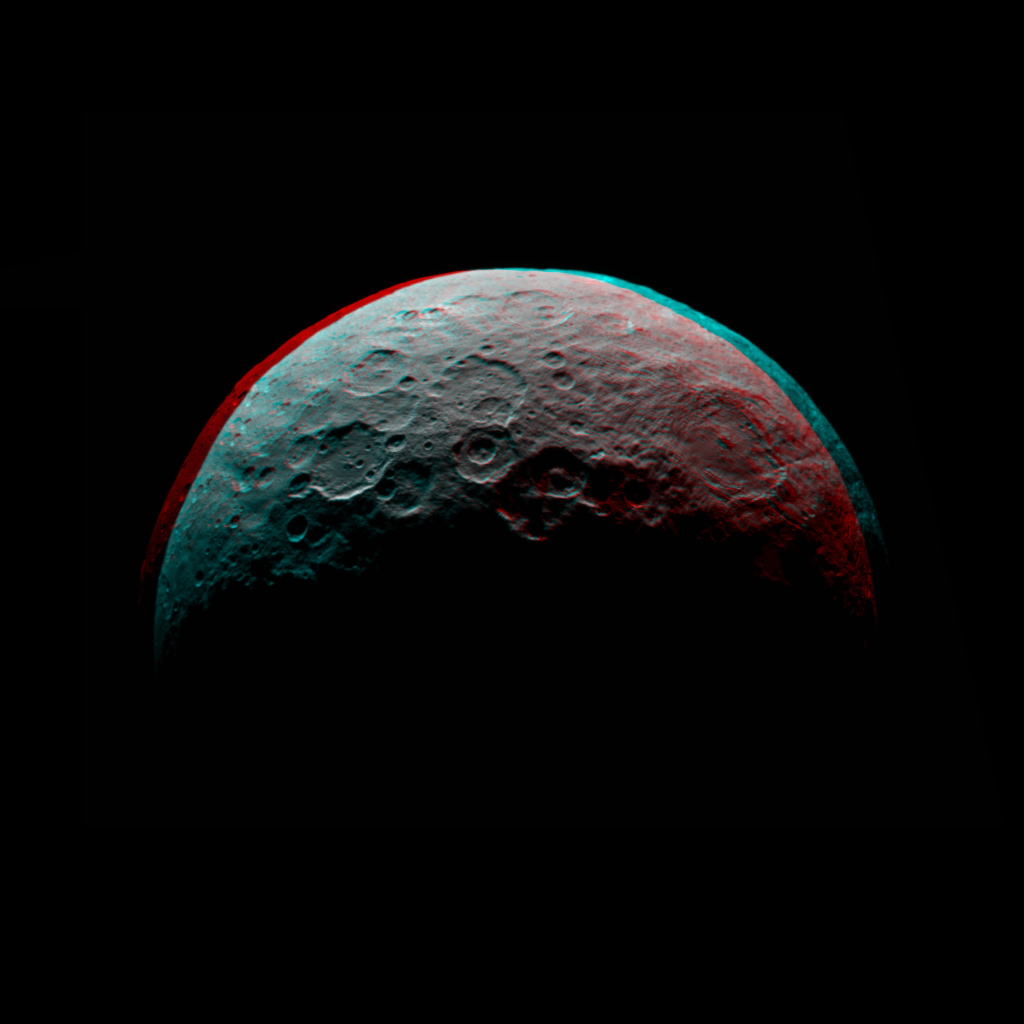

The spacecraft made most of its observations by looking straight down at the terrain directly beneath it. During portions of its first, second and fourth orbits, however, Dawn peered at the limb of Ceres against the endless black of space, seeing the sights from a different perspective to gain a better sense of the lay of the land.

And what marvels Dawn has beheld! How can you not be mesmerized by the luminous allure of the famous bright spots? They are not, in fact, a source of light, but for a reason that remains elusive, the ground there reflects much more sunlight than elsewhere. Still, it is easy to imagine them as radiating a light all their own, summoning space travelers from afar, beckoning the curious and the bold to venture closer in return for an attractive reward. And that is exactly what we will do, as we seek the rewards of new knowledge and new insights into the cosmos.

Although scientists have not yet determined what minerals are there, Dawn will gather much more data. As summarized in this table, our explorer will map Ceres again from much closer during the course of its orbital mission. New bright areas have shown up in other locations too, in some places as relatively small spots, in others as larger areas (as in the photo below), and all of them will come into sharper focus when Dawn descends further.

In the meantime, you can register your opinion for what the bright spots are. Join more than 100 thousand others who have voted for an explanation for this enigma. Of course, Ceres will be the ultimate arbiter, and nature rarely depends upon public opinion, but the Dawn project will consider sending the results of the poll to Ceres, courtesy of our team member on permanent assignment there.

In addition to the bright spots, Dawn's views from its present altitude have included a wide range of other intriguing sights, as one would expect on a world of more than one million square miles (nearly 2.8 million square kilometers). There are myriad craters excavated by objects falling from space, inevitable scars from inhabiting the main asteroid belt for more than four billion years, even for the largest and most massive resident there.

The craters exhibit a wide range of appearances, not only in size but also in how sharp and fresh or how soft and aged they look. Some display a peak at the center. A crater can form from such a powerful punch that the hard ground practically melts and flows away from the impact site. Then the material rebounds, almost as if it sloshes back, while already cooling and then solidifying again. The central peak is like a snapshot, preserving a violent moment in the formation of the crater. By correlating the presence or absence of central peaks with the sizes of the craters, scientists can infer properties of Ceres' crust, such as how strong it is. Rather than a peak at the center, some craters contain large pits, depressions that may be a result of gasses escaping after the impact. (Craters elsewhere in the solar system, including on Vesta and Mars, also have pits.)

Dawn also has spied many long, straight or gently curved canyons. Geologists have yet to determine how they formed, and it is likely that several different mechanisms are responsible. For example, some might turn out to be the result of the crust of Ceres shrinking as the heat and other energy accumulated upon formation gradually radiated into space. When the behemoth slowly cooled, stresses could have fractured the rocky, icy ground. Others might have been produced as part of the devastation when a space rock crashed, rupturing the terrain.

Ceres shows other signs of an active past rather than that of a static chunk of inert material passing the eons with little notice. Some areas are less densely cratered than others, suggesting that there are geological processes that erase the craters. Indeed, some regions look as if something has flowed over them, as if perhaps there was mud or slush on the surface.

In addition to evidence of aging and renewal, some powerful internal forces have uplifted mountains. One particularly striking structure is a steep cone that juts three miles (five kilometers) high in an otherwise relatively smooth area, looking to an untrained (but transfixed) eye like a volcanic cone, a familiar sight on your home planet (or, at least, on mine). No other isolated, prominent protuberance has been spotted on Ceres.

It is too soon for scientists to understand the intriguing geology of this ancient world, but the prolific adventurer is providing them with the information they will use. The bounty from this second mapping phase includes more than 1,600 pictures covering essentially all of Ceres, well over five million spectra in visible and infrared wavelengths and hundreds of hours of gravity measurements.

The spacecraft has performed its ambitious assignments quite admirably. Only a few deviations from the very elaborate plans occurred. On June 15 and 27, during the fourth and eighth flights over the dayside, the computer in the combination visible and infrared mapping spectrometer (VIR) detected an unexpected condition, and it stopped collecting data. When the spacecraft's main computer recognized the situation, it instructed VIR to close its protective cover and then power down. The unit dutifully did so. Also on June 27, about three hours before VIR's interruption, the camera's computer experienced something similar.

Most of the time that Dawn points its sensors at Ceres, it simultaneously broadcasts through one of its auxiliary radio antennas, casting a very wide but faint signal in the general direction of Earth. (As Dawn progresses in its orbit, the direction to Earth changes, but the spacecraft is equipped with three of these auxiliary antennas, each pointing in a different direction, and mission controllers program it to switch antennas as needed.) The operations team observed what had occurred in each case and recognized there was no need to take immediate action. The instruments were safe and Dawn continued to carry out all of its other tasks.

When Dawn subsequently flew to the nightside of Ceres and pointed its main antenna to Earth, it transmitted much more detailed telemetry. As engineers and scientists continue their careful investigations, they recognize that in many ways, these events appear very similar to ones that have occurred at other times in the mission.

Four years ago, VIR's computer reset when Dawn was approaching Vesta, and the most likely cause was deemed to be a cosmic ray strike. That's life in deep space! It also reset twice in the survey orbit phase at Vesta. The camera reset three times in the first three months of the low altitude mapping orbit at Vesta.

Even with the glitches in this second mapping orbit, Dawn's outstanding accomplishments represent well more than was originally envisioned or written into the mission's scientific requirements for this phase of the mission. For those of you who have not been to Ceres or aren't going soon (and even those of you who want to plan a trip there of your own), you can see what Dawn sees by going to the image gallery.

Although Dawn already has revealed far, far more about Ceres in the last six months than had been seen in the preceding two centuries of telescopic studies, the explorer is not ready to rest on its laurels. It is now preparing to undertake another complex spiral descent, using its sophisticated ion propulsion system to maneuver to a circular orbit three times as close to the dwarf planet as it is now. It will take five weeks to perform the intricate choreography needed to reach the third mapping altitude, starting tomorrow night. You can keep track of the spaceship's flight as it propels itself to a new vantage point for observing Ceres by visiting the mission status page or following it on Twitter @NASA_Dawn.

As Dawn moves closer to Ceres, Earth will be moving closer as well. Earth and Ceres travel on independent orbits around the sun, the former completing one revolution per year (indeed, that's what defines a year) and the latter completing one revolution in 4.6 years (which is one Cerean year). (We have discussed before why Earth revolves faster in its solar orbit, but in brief it is because being closer to the sun, it needs to move faster to counterbalance the stronger gravitational pull.) Of course, now that Dawn is in a permanent gravitational embrace with Ceres, where Ceres goes, so goes Dawn. And they are now and forever more so close together that the distance between Earth and Ceres is essentially equivalent to the distance between Earth and Dawn.

On July 22, Earth and Dawn will be at their closest since June 2014. As Earth laps Ceres, they will be 1.94 AU (180 million miles, or 290 million kilometers) apart. Earth will race ahead on its tight orbit around the sun, and they will be more than twice as far apart early next year.

Although Dawn communicates regularly with Earth, it left that planet behind nearly eight years ago and will keep its focus now on its new residence. With two very successful mapping campaigns complete, its next priority is to work its way down through Ceres' gravitational field to an altitude of about 900 miles (less than 1,500 kilometers). With sharper views and new kinds of observations (including stereo photography), the treasure trove obtained by this intrepid extraterrestrial prospector will only be more valuable. Everyone who longs for new understandings and new perspectives on the cosmos will grow richer as Dawn continues to pioneer at a mysterious and distant dwarf planet.

Dawn is 2,700 miles (4,400 kilometers) from Ceres. It is also 2.01 AU (187 million miles, or 301 million kilometers) from Earth, or 785 times as far as the moon and 1.98 times as far as the sun today. Radio signals, traveling at the universal limit of the speed of light, take 33 minutes to make the round trip.

Dr. Marc D. Rayman

10:00 p.m. PDT June 29, 2015

TAGS: DAWN, VESTA, CERES, DWARF PLANET, MISSION, SPACECRAFT, BRIGHT SPOTS

Dawn Journal | May 28, 2015

Mysteries Unravel as Dawn Circles Closer to Ceres

Dear Emboldawned Readers,

A bold adventurer from Earth is gracefully soaring over an exotic world of rock and ice far, far away. Having already obtained a treasure trove from its first mapping orbit, Dawn is now seeking even greater riches at dwarf planet Ceres as it maneuvers to its second orbit.

The first intensive mapping campaign was extremely productive. As the spacecraft circled 8,400 miles (13,600 kilometers) above the alien terrain, one orbit around Ceres took 15 days. During its single revolution, the probe observed its new home on five occasions from April 24 to May 8. When Dawn was flying over the night side (still high enough that it was in sunlight even when the ground below was in darkness), it looked first at the illuminated crescent of the southern hemisphere and later at the northern hemisphere.

When Dawn traveled over the sunlit side, it watched the northern hemisphere, then the equatorial regions, and finally the southern hemisphere as Ceres rotated beneath it each time. One Cerean day, the time it takes the globe to turn once on its axis, is about nine hours, much shorter than the time needed for the spacecraft to loop around its orbit. So it was almost as if Dawn hovered in place, moving only slightly as it peered down, and its instruments could record all of the sights as they paraded by.

We described the plans in much more detail in March, and they executed beautifully, yielding a rich collection of photos in visible and near infrared wavelengths, spectra in visible and infrared, and measurements of the strength of Ceres' gravitational attraction and hence its mass.

To gain the same view Dawn had, simply build your own ion-propelled spaceship, voyage deep into the main asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter, take up residence at the giant orb and look out the window. Or go to the image gallery here.

Either way, the sights are spectacular. And they have already gotten even better. As Dawn has been descending to its second mapping orbit, it paused ion-thrusting on May 16 and May 22 to take more pictures, helping navigators get a tight fix on its orbital location. We explained this technique of optical navigation earlier, but now it is slightly different. Dawn is so close to Ceres that the behemoth fills the camera's field of view. No longer charting Ceres' location relative to background stars, navigators now use distinctive features on Ceres itself. It was an indistinct, fuzzy little blob just a few months ago, but now the maps are becoming detailed and accurate. Mathematical analyses of the locations of specific landmarks in each picture allow navigators to determine where Dawn was when the picture was taken.

Let's see how this works. Suppose I gave you a picture I had taken in your house. (The last time I was there, I opted for the cover of darkness rather than a more visible demonstration of optical navigation, but we can still imagine.) Because you know the positions of the doors, windows, furniture, impact craters, paintings, etc., you could establish where I had been when I took the photo. Now that they have charted the positions of the features at Dawn's new home, navigators can do virtually the same thing.

In addition to aiding in celestial navigation, the photos provided still better views of the world Dawn traveled so long and so far to explore. Greater and greater detail is visible as Dawn orbits closer, and a tremendous variety of intriguing sights are coming into view. It may well be that the most interesting discoveries have not even been made yet, but for now, what captivates most people (and other readers as well) are the bright spots.

We have discussed them here and there in recent months, and their luminous power continues to dazzle us. What appeared initially as one fuzzy spot proved to be two smaller spots and now many even smaller regions as the focus has become sharper. Why the ground there reflects so much sunlight remains elusive. Dawn's finer examinations with its suite of sophisticated instruments in the second, third and then final mapping orbits will provide scientists with data they need to unravel this marvelous mystery. For now, the enigmatic lights present an irresistible cosmic invitation to go closer and to scrutinize this strange and wonderful world, and we are eager to accept. After all, we explore to learn, to know the unknown, and the uniquely powerful scientific method will reveal the nature of the bright areas and what they can tell us about the composition and geology of this complex dwarf planet.

› Full image and caption

After having been viewed as little more than a smudge in telescopes for more than two centuries since its discovery, Ceres now is seen as a detailed, three-dimensional world. As promised, measurements from Dawn have revised the size to be about 599 miles (963 kilometers) across at the equator. Like Earth and other planets, Ceres is oblate, or slightly wider at the equator than from pole to pole. The polar diameter is 554 miles (891 kilometers). These dimensions are impressively close to what astronomers had determined from telescopic observations and confirm Ceres to be the colossus we have described.

Before Dawn, scientists had estimated Ceres' mass to be 1.04 billion billion tons (947 billion billion kilograms). Now it is measured to be 1.03 billion billion tons (939 billion billion kilograms), well within the previous margin of error. It is an impressive demonstration of the success of science that astronomers had been able to determine the heft of that point of light so accurately. Nevertheless, even this small change of less than one percent is important for planning the rest of Dawn’s mission as it orbits closer and closer, feeling the gravitational tug ever more strongly.

Let's put this change in context. Dawn has now refined the mass, making a proportionally small adjustment of about 0.01 billion billion tons (eight billion billion kilograms). Although no more than a tweak on the overall value, it is still significantly greater than the combined mass of all asteroids visited by all other spacecraft. Ceres is so immense, so massive that even if all those asteroids were added to it, the difference would hardly even have been noticeable. This serves as another reminder that the dwarf planet really is quite unlike the millions of small asteroids that constitute the main asteroid belt. This behemoth contains about 30 percent of all the mass in that entire vast region of space. Vesta, the protoplanet Dawn orbited and studied in 2011-2012, is the second most massive resident there, holding about 8 percent of the asteroid belt's mass. Dawn by itself is exploring around 40 percent of the asteroid belt's mass!

Upon concluding its first mapping orbit, Dawn powered on its remarkable ion propulsion system on May 9 to fly down to a lower altitude where it will gain a better view. We examined the nature of the spiral paths between mapping orbits last year (and at Vesta in 2011-2012).

› Larger image

In its first mapping orbit, Dawn was 8,400 miles (13,600 kilometers) high, revolving once in 15.2 days at a speed of 150 mph (240 kilometers per hour). By the time it completes this descent, the probe will be at an altitude of 2,700 miles (4,400 kilometers), orbiting Ceres every 3.1 days at 254 mph (408 kilometers per hour). (All of the mapping orbits were summarized in this table.) We have discussed that lower orbits require greater velocity to counterbalance the stronger gravitational hold.

Dawn's uniquely capable ion propulsion system, with its extraordinary combination of efficiency and gentleness, propels the ship to its new orbital destination in just under four weeks. The descent requires five revolutions, each one faster than the one before. The flight profile is complicated, and sometimes Dawn even dips below the final, planned altitude and then rises to greater heights as it flies on a path that is temporarily elliptical. The overall trend, of course, is downward. As Dawn heads for its targeted circular orbit, its maneuvering is also generally reducing the orbit period, the time required to make one complete revolution around Ceres. Indeed, if Dawn stopped thrusting now, its orbit period would be about 83 hours, or 3.5 days.

Dawn will complete ion-thrusting on June 3, but it will not be ready to begin its next science observations then. Rather, as in the other new mapping orbits, the first order of business will be for navigators to measure the new orbital parameters accurately. The flight team then will install in Dawn's main computer the details of the orbit it achieved so it will always know its location.

In addition, the intensive campaign of observations is planned to begin when the robotic explorer travels from the night side to the day side over the north pole. With the three-day orbit period, that will next occur on June 5. Controllers will take advantage of the intervening time to conduct other activities, including routine maintenance of the two reaction wheels that remain operable, although they are powered off most of the time. (Two of the four failed years ago. Dawn no longer relies on these devices to control its orientation, and it is remarkable that the mission can accomplish all of its original objectives without them. But if two do function in the final mapping orbit later this year, they will help extend the spacecraft's lifetime for bonus studies.)

We have already presented the ambitious plans for this second mapping orbit, sometimes known as "the second mapping orbit" and sometimes more succinctly and confusingly as "survey orbit." As with all four of Dawn's mapping orbits, it is designed to take the spacecraft over the poles, ensuring the best possible coverage. The ship will fly from the north pole to the south over the side of Ceres facing the sun, and then loop back to the north over the side hidden in the deep dark of night. On the day side, Dawn will aim its camera and spectrometers at the lit ground, filling its memory to capacity with the readings. On the night side, it will point its main antenna to distant Earth in order to radio its findings home. At Dawn's altitude, Ceres will appear twice as wide as the camera's view. (As illustrated in this table, it will look about the size of a soccer ball seen from a yard, or a meter, away.) But as the dwarf planet rotates on its axis and Dawn sails around in its more leisurely orbit, eventually all of the landscape will come within sight of the instruments.

Only one noteworthy change has been made in the intricate plans for survey orbit since May 2014's shocking exposé. With the observations starting on June 5, the subsequent complex orbital flight to the third mapping orbit (also known as HAMO) would have begun on June 27. As we have seen, the rapidly changing orbit in the spiral descents requires a great deal of effort by the small operations team on a rigid schedule. The capable men and women flying Dawn accomplished the maneuvers flawlessly at Vesta and are well prepared for the challenges at Ceres. The work is very demanding, however, and so, just as at Vesta, the team has built into the strategy the capability to make adjustments to align most of the tasks with a conventional work schedule. The technical plans (even including the exquisitely careful husbanding of hydrazine following the loss of the two reaction wheels) fully account for such human factors. It turns out that leaving survey orbit three days later shifts a significant amount of the following work off weekends, making it more comfortable for the team members. Three days is one complete revolution, and always extracting as much from the mission as possible, they have devised another full set of observations for an eighth orbit. As a result, survey orbit may be even more extensive and productive than originally anticipated.

What awaits Dawn in the next mapping phase? The views will be three times as sharp as in the previous orbit, and exciting new discoveries are sure to come. What answers will be revealed? And what new questions (besides this one) will arise? We will know soon, as we all share in the thrill of this grand adventure. To help you keep track of Dawn's progress as it powers its way down and then conducts further observations, your correspondent writes brief (hard to believe, isn't it?) mission status updates. And although in space no one can hear you tweet, terrestrial followers can get even more frequent updates with information he provides for Twitter @NASA_Dawn.

Dawn is 3,400 miles (5,500 kilometers) from Ceres. It is also 2.30 AU (214 million miles, or 345 million kilometers) from Earth, or 855 times as far as the moon and 2.27 times as far as the sun today. Radio signals, traveling at the universal limit of the speed of light, take 38 minutes to make the round trip.

Dr. Marc D. Rayman

12:00 p.m. PDT May 28, 2015

TAGS: DAWN, CERES, VESTA, BRIGHT SPOTS, SPACECRAFT, MISSION

Dawn Journal | April 29, 2015

Getting Down to Science at Ceres

Let's get Dawn to business, Dear Readers,

Dawn's assignment when it embarked on its extraordinary extraterrestrial expedition in 2007 can be described quite simply: explore the two most massive uncharted worlds in the inner solar system. It conducted a spectacular mission at Vesta, orbiting the giant protoplanet for 14 months in 2011-2012, providing a wonderfully rich and detailed view. Now the sophisticated probe is performing its first intensive investigation of dwarf planet Ceres. Dawn is slowly circling the alien world of rock and ice, far from Earth and far from the sun, executing its complex operations with the prowess it has demonstrated throughout its ambitious journey.

Following an interplanetary trek of 7.5 years and 3.1 billion miles (4.9 billion kilometers), Earth's ambassador arrived in orbit on March 6, answering Ceres' two-century-old celestial invitation. With its advanced ion propulsion system and ace piloting skills, it has maneuvered extensively in orbit. Traveling mostly high over the night side of Ceres, arcing and banking, thrusting and coasting, accelerating and decelerating, climbing and diving, the spaceship flew to its first targeted orbital altitude, which it reached on April 23.

Dawn is at an altitude of about 8,400 miles (13,600 kilometers) above the mysterious terrain. This first mapping orbit is designated RC3 by the Dawn team and is a finalist in the stiff competition for the coveted title of Most Confusing Name for a Ceres Mapping Orbit. (See this table for the other contestants.) Last month we described some of the many observations Dawn will perform here, including comprehensive photography of the alien landscapes, spectra in infrared and visible wavelengths, a search for an extremely tenuous veil of water vapor and precise tracking of the orbit to measure Ceres' mass.

On the way down to this orbit, the spacecraft paused ion thrusting twice earlier this month to take pictures of Ceres, as it had seven times before in the preceding three months. (We presented and explained the schedule for photography during the three months leading up to RC3 here.) Navigators used the pictures to measure the position of Ceres against the background of stars, providing crucial data to guide the ship to its intended orbit. The Dawn team also used the pictures to learn about Ceres to aid in preparing for the more detailed observations.

We described last month, for example, adjusting the camera settings for upcoming pictures to ensure good exposures for the captivating bright spots, places that reflect significantly more sunlight than most of the dark ground. Scientists have also examined all the pictures for moons of Ceres (and many extra pictures were taken specifically for that purpose). And thanks to Dawn's pictures, everyone who longs for a perspective on the universe unavailable from our terrestrial home has been transported to a world one million times farther away than the International Space Station.

The final pictures before reaching RC3 certainly provide a unique perspective. (You can see Dawn's pictures of Ceres here.) On April 10 and April 14-15, Dawn peered down over the northern hemisphere and watched for two hours each time as Ceres turned on its axis, part of the unfamiliar cratered terrain bathed in sunlight, part in the deep dark of night. This afforded a very different view from what we are accustomed to in looking at other planets, as most depictions of planetary rotations are from nearer the equator to show more of the surface. (Indeed, Dawn acquired views like that in its February "rotation characterizations.") The latest animations of Ceres rotating beneath Dawn are powerful visual reminders that this capable interplanetary explorer really is soaring around in orbit about a distant, alien world. Following the complex flight high above the dark hemisphere, where there was nothing to see, the pictures also show us that the long night's journey into day has ended.

Gradually descending atop its blue-green beam of high velocity xenon ions, Dawn crossed over the terminator -- the boundary between the dark side and the lit side -- on April 15 almost directly over the north pole. On April 20, on final approach to RC3, it flew over the equator at an altitude of about 8,800 miles (14,000 kilometers).

The spacecraft completed its ion thrusting shortly after 1:00 a.m. PDT on April 23. What an accomplishment this was! From the time Dawn left its final mapping orbit at Vesta in July 2012, this is where it has been headed. The escape from Vesta's gravitational clutches in September 2012, the subsequent two and a half years of interplanetary travel and entering into orbit around Ceres on March 6, as genuinely exciting and important as it was, all really occurred as consequences of targeting this particular orbit.

In September 2014, the aftereffects of being struck by cosmic radiation compelled the operations team to rapidly develop a complex new approach trajectory because they still wanted to achieve this very orbit, where Dawn is now. And the eidetic reader will note that even when the innovative flight profile was presented five months ago (with many further details in subsequent months), we explained that it would conclude on April 23. And it did! Here we are! All the descriptions and figures plus a cool video elucidated a pretty neat idea, but it's also much more than an idea: it's real!! A probe from Earth is in a mapping orbit around a faraway dwarf planet.

When it had accomplished the needed ion thrusting, the veteran space traveler turned to point its main antenna to Earth so mission controllers could prepare it for the intensive mapping observations. The first task was to measure the orbital parameters so they could be transmitted to the spacecraft.

A few readers (you and I both know who you are) may have noted that in Dawn Journals during the last year, we have described the altitude of RC3 as 8,400 miles and 13,500 kilometers. Above, however, it is 13,600 kilometers. This is not a mistake. (It would be a mistake if the previous sentence were written, "Above, howevr, it is 13,600 kilometers.") This subtle difference belies several important issues about the orbits at Ceres. Let's take a further look.

As we explained when Dawn resided at Vesta, the orbital altitude we present is always an average (and rounded off, to avoid burdening readers with too many unhelpful digits). Vesta, Ceres, Earth and other planetary bodies are not perfect spheres, so even if the spacecraft traveled in a perfect circle, its altitude would change. They all are somewhat oblate, being wider across the equator than from pole to pole. In addition, they have more localized topography. Think of flying in a plane over your planet. If the pilot maintains a constant altitude above sea level, the distance above the ground changes because the elevation of the ground itself varies, coming closer to the aircraft on mountains and farther in valleys. In addition, as it turns out, orbits are not perfect circles but tend to be slightly elliptical, as if the plane flies slightly up and down occasionally, so the altitude changes even more.

In their exquisitely detailed planning, the Dawn team has had to account for the unknown nature of Ceres itself, including its mass and hence the strength of its gravitational pull. Dawn is the only spacecraft to orbit large, massive planetary bodies that were not previously visited by flyby spacecraft. Mercury, Venus, the moon, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn all were studied by spacecraft that flew past them before subsequent missions were sent to orbit them. The first probes to each provided an initial measurement of the mass and other properties that were helpful for the arrival of the first orbiters. At Vesta and Ceres, Dawn has had to discover the essential characteristics as it spirals in closer and closer. For each phase, engineers make the best measurements they can and then use them to update the plans for the subsequent phases. As a result, however, plans are based on impressive but nevertheless imperfect knowledge of what will be encountered at lower altitudes. So even if the spacecraft executes an ion thrust flight profile perfectly, it might not wind up exactly where the plan had specified.

There are other reasons as well for small differences between the predicted and the actual orbit. One is minor variations in the thrust of the ion propulsion system, as we discussed here. Another is that every time the spacecraft fires one of its small rocket thrusters to rotate or to stabilize its orientation in the zero-gravity conditions of spaceflight, that also nudges the spacecraft, changing its orbit a little. (See here for a related example of the effect of the thrusters on the trajectory.)

The Dawn flight team has a deep understanding of all the sources of orbit discrepancies, and they always ensure that their intricate plans account for them. Even if the RC3 altitude ended up more than 300 miles (500 kilometers) higher or lower than the specified value, everything would still work just fine to yield the desired pictures and other data. In fact, the actual RC3 orbit is within 25 miles (40 kilometers), or less than one tenth what the plan was designed to accommodate, so the spacecraft achieved a virtual cosmic bullseye!

In the complex preparations on April 23, one file was not radioed to Dawn on time, so late that afternoon when the robot tried to use this file, it could not find it. It responded appropriately by running protective software, stopping its activities, entering "safe mode" and beaming a signal back to distant Earth to indicate it needed further instructions. After the request arrived in mission control at JPL, engineers quickly recognized what had occurred. That night they reconfigured the spacecraft out of safe mode and back to its normal operational configuration, and they finished off the supply of ice cream in the freezer just outside the mission control room. Although Dawn was not ready to begin its intensive observation campaign in the morning of April 24, it started later that same day and has continued to be very productive.

Dawn is a mission of exploration. And rather than be constrained by a fast flight by a target for a brief glimpse, Dawn has the capability to linger in orbit for a very long time at close range. The probe will spend more than a year conducting detailed investigations to reveal as much as possible about the nature of the first dwarf planet discovered, which we had seen only with telescopes since it was first glimpsed in 1801. The pictures Dawn has sent us so far are intriguing and entrancing, but they are only the introduction to this exotic world. They started transforming it from a smudge of light into a real, physical place and one that a sophisticated, intrepid spacecraft can even reach. Being in the first mapping orbit represents the opportunity now to begin developing a richly detailed, intimate portrait of a world most people never even knew existed. Now, finally, we are ready to start uncovering the secrets Ceres has held since the dawn of the solar system.

Dawn is 8,400 miles (13,600 kilometers) from Ceres. It is also 2.66 AU (247 million miles, or 398 million kilometers) from Earth, or 985 times as far as the moon and 2.64 times as far as the sun today. Radio signals, traveling at the universal limit of the speed of light, take 44 minutes to make the round trip.

Dr. Marc D. Rayman

10:30 p.m. PDT April 29, 2015

P.S. Our expert outreach team has done a beautiful job modernizing the website, and blog comments are no longer included. I appreciate all the very kind feedback, expressions of enthusiasm, interesting questions and engaging discussions that the community of Dawnophiles has posted over the last year or so. Now I will devote the time I had been spending responding to comments to providing more frequent mission status updates as well as fun and interesting tidbits you can follow on Twitter @NASA_Dawn.

TAGS: DAWN, CERES, BRIGHT SPOT, SPACECRAFT, MISSION

Dawn Journal | March 31, 2015

Let the Discoveries Begin: A Guide to Dawn's Exploration of Dwarf Planet Ceres

Dear Dawnticipating Explorers,

Now orbiting high over the night side of a dwarf planet far from Earth, Dawn arrived at its new permanent residence on March 6. Ceres welcomed the newcomer from Earth with a gentle but firm gravitational embrace. The goddess of agriculture will never release her companion. Indeed, Dawn will only get closer from now on. With the ace flying skills it has demonstrated many times on this ambitious deep-space trek, the interplanetary spaceship is using its ion propulsion system to maneuver into a circular orbit 8,400 miles (13,500 kilometers) above the cratered landscape of ice and rock. Once there, it will commence its first set of intensive observations of the alien world it has traveled for so long and so far to reach.

For now, however, Dawn is not taking pictures. Even after it entered orbit, its momentum carried it to a higher altitude, from which it is now descending. From March 2 to April 9, so much of the ground beneath it is cloaked in darkness that the spacecraft is not even peering at it. Instead, it is steadfastly looking ahead to the rewards of the view it will have when its long, leisurely, elliptical orbit loops far enough around to glimpse the sunlit surface again.

Among the many sights we eagerly anticipate are those captivating bright spots. Hinted at more than a decade ago by Hubble Space Telescope, Dawn started to bring them into sharper focus after an extraordinary journey of more than seven years and three billion miles (nearly five billion kilometers). Although the spots are reflections of sunlight, they seem almost to radiate from Ceres as cosmic beacons, drawing us forth, spellbound. Like interplanetary lighthouses, their brilliant glow illuminates the way for a bold ship from Earth sailing on the celestial seas to a mysterious, uncharted port. The entrancing lights fire our imagination and remind us of the irresistible lure of exploration and the powerful anticipation of an adventure into the unknown.

As we describe below, Dawn’s extensive photographic coverage of the sunlit terrain in early May will include these bright spots. They will not be in view, however, when Dawn spies the thin crescent of Ceres in its next optical navigation session, scheduled for April 10 (as always, all dates here are in the Pacific time zone).

As the table here shows, on April 14 (and extending into April 15), Dawn will obtain its last navigational fix before it finishes maneuvering. Should we look forward to catching sight of the bright spots then? In truth, we do not yet know. The spots surely will be there, but the uncertainty is exactly where “there” is. We still have much to learn about a dwarf planet that, until recently, was little more than a fuzzy patch of light among the glowing jewels of the night sky. (For example, only last month did we determine where Ceres’north and south poles point.) Astronomers had clocked the length of its day, the time it takes to turn once on its axis, at a few minutes more than nine hours. But the last time the spots were in view of Dawn’s camera was on Feb. 19. From then until April 14, while Earth rotates more than 54 times (at 24 hours per turn), Ceres will rotate more than 140 times, which provides plenty of time for a small discrepancy in the exact rate to build up. To illustrate this, if our knowledge of the length of a Cerean day were off by one minute (or less than 0.2 percent), that would translate into more than a quarter of a turn during this period, drastically shifting the location of the spots from Dawn’s point of view. So we are not certain exactly what range of longitudes will be within view in the scheduled OpNav 7 window. Regardless, the pictures will serve their intended purpose of helping navigators establish the probe’s location in relation to its gravitational captor.

Dawn’s gradual, graceful arc down to its first mapping orbit will take the craft from the night side to the day side over the north pole, and then it will travel south. It will conclude its powered flight over the sunlit terrain at about 60 degrees south latitude. The spacecraft will finish reshaping its orbit on April 23, and when it stops its ion engine on that date, it will be in its new circular orbit, designated RC3. (We will return to the confusing names of the different orbits at Ceres below.) Then it will coast, just as the moon coasts in orbit around Earth and Earth coasts around the sun. It will take Dawn just over 15 days to complete one revolution around Ceres at this height. We had a preview of RC3 last year, and now we can take an updated look at the plans.

The dwarf planet is around 590 miles (950 kilometers) in diameter (like Earth and other planets, however, it is slightly wider at the equator than from pole to pole). At the spacecraft’s orbital altitude, it will appear to be the same size as a soccer ball seen from 10 feet (3 meters) away. Part of the basis upon which mission planners chose this distance for the first mapping campaign is that the visible disc of Ceres will just fit in the camera’s field of view. All the pictures taken at lower altitudes will cover a smaller area (but will be correspondingly more detailed). The photos from RC3 will be 3.4 times sharper than those in RC2.

There will be work to do before photography begins however. The first order of business after concluding ion thrusting will be for the flight team to perform a quick navigational update (this time, using only the radio signal) and transmit any refinements (if necessary) in Dawn’s orbital parameters, so it always has an accurate knowledge of where it is. (These will not be adjustments to the orbit but rather a precise mathematical description of the orbit it achieved.) Controllers will also reconfigure the spacecraft for its intensive observations, which will commence on April 24 as it passes over the south pole and to the night side again.

As at Vesta, even though half of each circular orbit will be over the night side of Ceres, the spacecraft itself will never enter the shadows. The operations team has carefully designed the orbits so that at Dawn’s altitude, it remains illuminated by the sun, even when the land below is not.

It may seem surprising (or even be surprising) that Dawn will conduct measurements when the ground directly beneath it is hidden in the deep darkness of night. To add to the surprise, these observations were not even envisioned when Dawn’s mission was designed, and it did not perform comparable measurements during its extensive exploration of Vesta in 2011-2012.

The measurements on the night side will serve several purposes. One of the many sophisticated techniques scientists use to elucidate the nature of planetary surfaces is to measure how much light they reflect at different angles. Over the course of the next year, Dawn will acquire tens of thousands of pictures from the day side of Ceres, when, in essence, the sun is behind the camera. When it is over the night side in RC3, carefully designed observations of the lit terrain (with the sun somewhat in front of the camera, although still at a safe angle) will significantly extend the range of angles.

In December, we described the fascinating discovery of an extremely diffuse veil of water vapor around Ceres. How the water makes its way from the dwarf planet high into space is not known. The Dawn team has devised a plan to investigate this further, even though the tiny amount of vapor was sighted long after the explorer left Earth equipped with sensors designed to study worlds without atmospheres.

It is worth emphasizing that the water vapor is exceedingly tenuous. Indeed, it is much less dense than Earth’s atmosphere at altitudes above the International Space Station, which orbits in what most people consider to be the vacuum of space. Our hero will not need to deploy its umbrella. Even comets, which are miniscule in comparison with Ceres, liberate significantly more water.

There may not even be any water vapor at all now because Ceres is farther from the sun than when the Herschel Space Observatory saw it, but if there is, detecting it will be very challenging. The best method to glimpse it is to look for its subtle effects on light passing through it. Although Dawn cannot gaze directly at the sun, it can look above the lit horizon from the night side, searching intently for faint signs of sunlight scattered by sparse water molecules (or perhaps dust lofted into space with them).

For three days in RC3 after passing over the south pole, the probe will take many pictures and visible and infrared spectra as it watches the slowly shrinking illuminated crescent and the space over it. When the spacecraft has flown to about 29 degrees south latitude over the night side, it will no longer be safe to aim its sensitive instruments in that direction, because they would be too close to the sun. With its memory full of data, Dawn will turn to point its main antenna toward distant Earth. It will take almost two days to radio its findings to NASA’s Deep Space Network. Meanwhile, the spacecraft will continue northward, gliding silently high over the dark surface.

On April 28, it will rotate again to aim its sensors at Ceres and the space above it, resuming measurements when it is about 21 degrees north of the equator and continuing almost to the north pole on May 1. By the time it turns once again to beam its data to Earth, it will have completed a wealth of measurements not even considered when the mission was being designed.

Loyal readers will recall that Dawn has lost two of its four reaction wheels, gyroscope-like devices it uses to turn and to stabilize itself. Although such a loss could be grave for some missions, the operations team overcame this very serious challenge. They now have detailed plans to accomplish all of the original Ceres objectives regardless of the condition of the reaction wheels, even the two that have not failed (yet). It is quite a testament to their creativity and resourcefulness that despite the tight constraints of flying the spacecraft differently, the team has been able to add bonus objectives to the mission.

Dawn will finish transmitting its data after its orbit takes it over the north pole and to the day side of Ceres again. For three periods during its gradual flight of more than a week over the illuminated landscape, it will take pictures (in visible and near-infrared wavelengths) and spectra. Each time, it will look down from space for a full Cerean day, watching for more than nine hours as the dwarf planet pirouettes, as if showing off to her new admirer. As the exotic features parade by, Dawn will faithfully record the sites.

It is important to set the camera exposures carefully. Most of the surface reflects nine percent of the sunlight. (For comparison, the moon reflects 12 percent on average, although as many Earthlings have noticed, there is some variation from place to place. Mars reflects 17 percent, and Vesta reflects 42 percent. Many photos seem to show that your correspondent’s forehead reflects about 100 percent.) But there are some small areas that are significantly more reflective, including the two most famous bright spots. Each spot occupies only one pixel (2.7 miles, or 4.3 kilometers across) in the best pictures so far. If each bright area on the ground is the size of a pixel, then they reflect around 40 percent of the light, providing the stark contrast with the much darker surroundings. When Dawn’s pictures show more detail, it could be that they will turn out to be even smaller and even more reflective than they have appeared so far. In RC3, each pixel will cover 0.8 miles (1.3 kilometers). To ensure the best photographic results, controllers are modifying the elaborate instructions for the camera to take pictures of the entire surface with a wider range of exposures than previously planned, providing high confidence that all dark and all bright areas will be revealed clearly.

Dawn will observe Ceres as it flies from 45 degrees to 35 degrees north latitude on May 3-4. Of course, the camera’s view will extend well north and south of the point immediately below it. (Imagine looking at a globe. Even though you are directly over one point, you can see a larger area.) The territory it will inspect will include those intriguing bright spots. The explorer will report back to Earth on May 4-5. It will perform the same observations between 5 degrees north and 5 degrees south on May 5-6 and transmit those findings on May 6-7. To complete its first global map, it will make another full set of measurements for a Cerean day as it glides between 35 degrees and 45 degrees south on May 7.

By the time it has transmitted its final measurements on May 8, the bounty from RC3 may be more than 2,500 pictures and two million spectra. Mission controllers recognize that glitches are always possible, especially in such complex activities, and they take that into account in their plans. Even if some of the scheduled pictures or spectra are not acquired, RC3 should provide an excellent new perspective on the alien world, displaying details three times smaller than what we have discerned so far.

Dawn activated its gamma ray spectrometer and neutron spectrometer on March 12, but it will not detect radiation from Ceres at this high altitude. For now, it is measuring space radiation to provide context for later measurements. Perhaps it will sense some neutrons in the third mapping orbit this summer, but its primary work to determine the atomic constituents of the material within about a yard (meter) of the surface will be in the lowest altitude orbit at the end of the year.

Dawn will conduct its studies from three lower orbital altitudes after RC3, taking advantage of the tremendous maneuverability provided by ion propulsion to spiral from one to another. We presented previews last year of each phase, and as each approaches, we will give still more up-to-date details, but now that Dawn is in orbit, let’s summarize them here. Of course, with complicated operations in the forbidding depths of space, there are always possibilities for changes, especially in the schedule. The team has developed an intricate but robust and flexible plan to extract as many secrets from Ceres as possible, and they will take any changes in stride.

Each orbit is designed to provide a better view than the one before, and Dawn will map the orb thoroughly while at each altitude. The names for the orbits – rotation characterization 3 (RC3); survey; high altitude mapping orbit (HAMO); and low altitude mapping orbit (LAMO) – are based on ancient ideas, and the origins are (or should be) lost in the mists of time. Readers should avoid trying to infer anything at all meaningful in the designations. After some careful consideration, your correspondent chose to use the same names the Dawn team uses rather than create more helpful descriptors for the purposes of these blogs. That ensures consistency with other Dawn project communications. After all, what is important is not what the different orbits are called but rather what amazing new discoveries each one enables.

The robotic explorer will make many kinds of measurements with its suite of powerful instruments. As one indication of the improving view, this table includes the resolution of the photos, and the ever finer detail may be compared with the pictures during the approach phase. For another perspective, we extend the soccer ball analogy above to illustrate how large Ceres will appear to be from the spacecraft’s orbital vantage point.

As Dawn orbits Ceres, together they orbit the sun. Closer to the master of the solar system, Earth (with its own retinue, including the moon and many artificial satellites) travels faster in its heliocentric orbit because of the sun’s stronger gravitational pull at its location. In December, Earth was on the opposite side of the sun from Dawn, and now the planet’s higher speed is causing their separation to shrink. Earth will get closer and closer until July 22, when it will pass on the inside track, and the distance will increase again.

In the meantime, on April 12, Dawn will be equidistant from the sun and Earth. The spacecraft will be 2.89 AU or 269 million miles (433 million kilometers) from both. At the same time, Earth will be 1.00 AU or 93.2 million miles (150 million kilometers) from the sun.

It will be as if Dawn is at the tip of a giant celestial arrowhead, pointing the way to a remarkable solar system spectacle. The cosmos should take note! Right there, a sophisticated spaceship from Earth is gracefully descending on a blue-green beam of xenon ions. Finally, the dwarf planet beneath it, a remote remnant from the dawn of the solar system, is lonely no more. Almost 4.6 billion years after it formed, and 214 years after inquisitive creatures on a distant planet first caught sight of it, a mysterious world is still welcoming the new arrival. And as Dawn prepares to settle into its first close orbit, ready to discover secrets Ceres has kept for so long, everyone who shares in the thrill of this grand and noble adventure eagerly awaits its findings. Together, we look forward to the excitement of new knowledge, new insight and new fuel for our passionate drive to explore the universe.

Dawn is 35,000 miles (57,000 kilometers) from Ceres, or 15 percent of the average distance between Earth and the moon. It is also 3.04 AU (282 million miles, or 454 million kilometers) from Earth, or 1,120 times as far as the moon and 3.04 times as far as the sun today. Radio signals, traveling at the universal limit of the speed of light, take 51 minutes to make the round trip.

Dr. Marc D. Rayman

6:00 p.m. PDT March 31, 2015

› Read more entries from Marc Rayman's Dawn Journal

TAGS: DAWN, CERES, VESTA, DWARF PLANET, SPACECRAFT, MISSION

Dawn Journal | March 6, 2015

We Did It! Dawn Arrives at Dwarf Planet Ceres

Dear Unprecedawnted Readers,

Since its discovery in 1801, Ceres has been known as a planet, then as an asteroid, and later as a dwarf planet. Now, after a journey of 3.1 billion miles (4.9 billion kilometers) and 7.5 years, Dawn calls it “home.”

Earth’s robotic emissary arrived at about 4:39 a.m. PST today. It will remain in residence at the alien world for the rest of its operational life, and long, long after.

Before we delve into this unprecedented milestone in the exploration of space, let’s recall that even before reaching orbit, Dawn started taking pictures of its new home. Last month we presented the updated schedule for photography. Each activity to acquire images (as well as visible spectra and infrared spectra) has executed smoothly and provided us with exciting and tantalizing new perspectives.

While there are countless questions about Ceres, the most popular now seems to be what the bright spots are. It is impossible not to be mesmerized by what appear to be glowing beacons, shining out across the cosmic seas from the uncharted lands ahead. But the answer hasn’t changed: we don’t know. There are many intriguing speculations, but we need more data, and Dawn will take photos and myriad other measurements as it spirals closer and closer during the year. For now, we simply know too little.

For example, some people ask if those spots might be lights from an alien city. That’s ridiculous! At this early stage, how could Dawn determine what kinds of groupings Cereans live in? Do they even have cities? For all we know, they may live only in rural communities, or perhaps they only have large states.

What we already know is that in more than 57 years of space exploration, Dawn is now the only spacecraft ever to orbit two extraterrestrial destinations. A true interplanetary spaceship, Dawn left Earth in Sep. 2007 and traveled on its own independent course through the solar system. It flew past Mars in Feb. 2009, robbing the red planet of some of its own orbital energy around the sun. In July 2011, the ship entered orbit around the giant protoplanet Vesta, the second most massive object in the main asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter. (By the way, Dawn’s arrival at Vesta was exactly one Vestan year ago earlier this week.) It conducted a spectacular exploration of that fascinating world, showing it to be more closely related to the terrestrial planets (including Earth, home to many of our readers) than to the typical objects people think of as asteroids. After 14 months of intensive operations at Vesta, Dawn climbed out of orbit in Sep. 2012, resuming its interplanetary voyage. Today it arrived at its final destination, Ceres, the largest object between the sun and Pluto that had not previously been visited by a spacecraft. (Fortunately, New Horizons is soon to fly by Pluto. We are in for a great year!)

What was the scene like at JPL for Dawn’s historic achievement? It’s easy to imagine the typical setting in mission control. The tension is overwhelming. Will it succeed or will it fail? Anxious people watch their screens, monitoring telemetry carefully, frustrated that there is nothing more they can do now. Nervously biting their nails, they are thinking of each crucial step, any one of which might doom the mission to failure. At the same time, the spacecraft is executing a bone-rattling, whiplash-inducing burn of its main engine to drop into orbit. When the good news finally arrives that orbit is achieved, the room erupts! People jump up and down, punch the air, shout, tweet, cry, hug and feel the tremendous relief of overcoming a huge risk. You can imagine all that, but that’s not what happened.

If you had been in Dawn mission control, the scene would have been different. You would mostly be in the dark. (For your future reference, the light switches are to the left of the door.) The computer displays would be off, and most of the illumination would be from the digital clock and the string of decorative blue lights that indicate the ion engine is scheduled to be thrusting. You also would be alone (at least until JPL Security arrived to escort you away, because you were not cleared to enter the room, and, for that matter, how did you get past the electronic locks?). Meanwhile, most of the members of the flight team were at home and asleep! (Your correspondent was too, rare though that is. When Dawn entered orbit around Vesta, he was dancing. Ceres’ arrival happened to be at a time less conducive to consciousness.)

Why was such a significant event treated with somnolence? It is because Dawn has a unique way of entering orbit, which is connected with the nature of the journey itself. We have discussed some aspects of getting into orbit before (with this update to the nature of the approach trajectory). Let’s review some of it here.

It may be surprising that prior to Dawn, no spacecraft had even attempted to orbit two distant targets. Who wouldn’t want to study two alien worlds in detail, rather than, as previous missions, either fly by one or more for brief encounters or orbit only one? A mission like Dawn’s is an obvious kind to undertake. It happens in science fiction often: go somewhere, do whatever you need to do there (e.g., beat someone up or make out with someone) and then boldly go somewhere else. However, science fact is not always as easy as science fiction. Such missions are far, far beyond the capability of conventional propulsion.

Deep Space 1 (DS1) blazed a new trail with its successful testing of ion propulsion, which provides 10 times the efficiency of standard propulsion, showing on an operational interplanetary mission that the advanced technology really does work as expected. (This writer was fortunate enough to work on DS1, and he even documented the mission in a series of increasingly wordy blogs. But he first heard of ion propulsion from the succinct Mr. Spock and subsequently followed its use by the less logical Darth Vader.)

Dawn’s ambitious expedition would be truly impossible without ion propulsion. (For a comparison of chemical and ion propulsion for entering orbit around Mars, an easier destination to reach than either Vesta or Ceres, visit this earlier log.) So far, our advanced spacecraft has changed its own velocity by 23,800 mph (38,400 kilometers per hour) since separating from its rocket, far in excess of what any other mission has achieved propulsively. (The previous record was held by DS1.)

Dawn is exceptionally frugal in its use of xenon propellant. In this phase of the mission, the engine expends only a quarter of a pound (120 grams) per day, or the equivalent of about 2.5 fluid ounces (75 milliliters) per day. So although the thrust is very efficient, it is also very gentle. If you hold a single sheet of paper in your hand, it will push on your hand harder than the ion engine pushes on the spacecraft at maximum thrust. At today’s throttle level, it would take the distant explorer almost 11 days to accelerate from zero to 60 mph (97 kilometers per hour). That may not evoke the concept of a drag racer. But in the zero-gravity, frictionless conditions of spaceflight, the effect of this whisper-like thrust can build up. Instead of thrusting for 11 days, if we thrust for a month, or a year, or as Dawn already has, for more than five years, we can achieve fantastically high velocity. Ion propulsion delivers acceleration with patience.

Most spacecraft coast most of the time, following their repetitive orbits like planets do. They may use the main engine for a few minutes or perhaps an hour or two throughout the entire mission. With ion propulsion, in contrast, the spacecraft may spend most of its time in powered flight. Dawn has flown for 69% of its time in space emitting a cool blue-green glow from one of its ion engines. (With three ion engines, Dawn outdoes the Star Wars TIE (twin ion engine) fighters.)

The robotic probe uses its gentle thrust to gradually reshape its path through space rather than simply following the natural course that a planet would. After it escaped from Vesta’s gravitational clutches, it slowly spiraled outward from the sun, climbing the solar system hill, making its heliocentric orbit more and more and more like Ceres’. By the time it was in the vicinity of the dwarf planet today, both were traveling around the sun at more than 38,600 mph (62,100 kilometers per hour). Their trajectories were nearly identical, however, so the difference in their speeds was only 100 mph (160 kilometers per hour), or less than 0.3 percent of the total. Flying like a crackerjack spaceship pilot, Dawn elegantly used the light touch of its ion engine to be at a position and velocity that it could ease gracefully into orbit. At a distance of 37,700 miles (60,600 kilometers), Ceres reached out and tenderly took the newcomer from Earth into its permanent gravitational embrace.

If you had been in space watching the event, you would have been cold, hungry and hypoxic. But it would not have looked much different from the 1,885 days of ion thrust that had preceded it. The spacecraft was perched atop its blue-green pillar of xenon ions, patiently changing its course, as it does for so much of quiet cruise. But now, at one moment it was flying too fast for Ceres’ gravity to hang on to it, and the next moment it had slowed just enough that it was in orbit. Had it stopped thrusting at that point, it would have continued looping around the dwarf planet. But it did not stop. Instead, it is working now to reshape its orbit around Ceres. As we saw in November, its orbital acrobatics first will take it up to an altitude of 47,000 miles (75,000 kilometers) on March 19 before it swoops down to 8,400 miles (13,500 kilometers) on April 23 to begin its intensive observations in the orbit designated RC3.

In fact, Dawn’s arrival today really is simply a consequence of the route it is taking to reach that lower orbit next month. Navigators did not aim for arriving today. Rather, they plotted a course that began at Vesta and goes to RC3 (with a new design along the way), and it happens that the conditions for capture into orbit occurred this morning. As promised last month, we present here a different view of the skillful maneuvering by this veteran space traveler.

If Dawn had stopped thrusting before Ceres could exert its gravitational control, it wouldn’t have flown very far away. The spacecraft had already made their paths around the sun very similar, and the ion propulsion system provides such exceptional flexibility to the mission that controllers could have guided it into orbit some other time. This was not a one-time, all-or-nothing event.

So the flight team was not tense. They had no need to observe it or make a spectacle out of it. Mission control remained quiet. The drama is not in whether the mission will succeed or fail, in whether a single glitch could cause a catastrophic loss, in whether even a tiny mistake could spell doom. Rather, the drama is in the opportunity to unveil the wonderful secrets of a fascinating relict from the dawn of the solar system more than 4.5 billion years ago, a celestial orb that has beckoned for more than two centuries, the first dwarf planet discovered.

Dawn usually flies with its radio transmitter turned off (devoting its electricity instead to the power-hungry ion engine), and so it entered orbit silently. As it happened, a routine telecommunications session was scheduled about an hour after attaining orbit, at 5:36 a.m. PST. (It’s only coincidence it was that soon. At Vesta, it was more than 25 hours between arrival and the next radio contact.) For primary communications, Dawn pauses thrusting to point its main antenna to Earth, but other times, as in this case, it is programmed to use one of its auxiliary antennas to transmit a weaker signal without stopping its engine, whispering just enough for engineers to verify that it remains healthy.

The Deep Space Network’s exquisitely sensitive 230-foot (70-meter) diameter antenna in Goldstone, Calif., picked up the faint signal from across the solar system on schedule and relayed it to Dawn mission control. One person was in the room (and yes, he was cleared to enter). He works with the antenna operator to ensure the communications session goes smoothly, and he is always ready to contact others on the flight team if any anomalies arise. In this case, none did, and it was a quiet morning as usual. The mission director checked in with him shortly after the data started to trickle in, and they had a friendly, casual conversation that included discussing some of the telemetry that indicated the spacecraft was still performing its routine ion thrusting. The determination that Dawn was in orbit was that simple. Confirming that it was following its flight plan was all that was needed to know it had entered orbit. This beautifully choreographed celestial dance is now a pas de deux.

As casual and tranquil as all that sounds, and as logical and systematic as the whole process is, the reality is that the mission director was excited. There was no visible hoopla, no audible fanfare, but the experience was powerful fuel for the passionate fires that burn within.

As soundlessly as a spacecraft gliding through the void, the realization emerges …

Dawn made it!!

It is in orbit around a distant world!!

Yes, it’s clear from the technical details, but it is more intensely reflected in the silent pounding of a heart that has spent a lifetime yearning to know the cosmos. Years and years of hard work devoted to this grand undertaking, constant hopes and dreams and fears of all possible futures, uncounted challenges (some initially appearing insurmountable) and a seeming infinitude of decisions along the way from early concepts through a real interplanetary spacecraft flying on an ion beam beyond the sun.

And then, a short, relaxed chat over a few bits of routine data that report the same conditions as usual on the distant robot. But today they mean something different.

They mean we did it!!

Everyone on the team will experience the news that comes in a congratulatory email in their own way, in the silence and privacy of their own thoughts. But it means the same to everyone.

We did it!!

And it’s not only the flight team. Humankind!! With our relentless curiosity, our insatiable hunger for knowledge, our noble spirit of adventure, we all share in the experience of reaching out from our humble home to the stars.

Together, we did it!!!

It was a good way to begin the day. It was Dawn at Ceres.

Let’s bring into perspective the cosmic landscape on which this remarkable adventure is now taking place. Imagine Earth reduced to the size of a soccer ball. On this scale, the International Space Station would orbit at an altitude of a bit more than one-quarter of an inch (seven millimeters). The moon would be a billiard ball almost 21 feet (6.4 meters) away. The sun, the conductor of the solar system orchestra, would be 79 feet (24 meters) across at a distance of 1.6 miles (2.6 kilometers). But even more remote, Dawn would be 5.3 miles (8.6 kilometers) away. (Just a few months ago, when the spacecraft was on the opposite side of the sun from Earth, it would have been more than six miles, or almost 10 kilometers, from the soccer ball.) Tremendously far now from its erstwhile home, it would be only a little over a yard (a meter) from its new residence. (By the end of this year, Dawn will be slightly closer to it than the space station is to Earth, a quarter of an inch, or six millimeters.) That distant world, Ceres, the largest object between Mars and Jupiter, would be five-eighths of an inch (1.6 centimeters) across, about the size of a grape. Of course a grape has a higher water content than Ceres, but we can be sure that exploring this intriguing world of rock and ice will be much sweeter!

As part of getting to know its new neighborhood, Dawn has been hunting for moons of Ceres. Telescopic studies had not revealed any, but if there were a moon smaller than about half a mile (one kilometer), it probably would not have been discovered. The spacecraft’s unique vantage point provides an opportunity to look for any that might have escaped detection. Many pictures have been taken specifically for this purpose, and scientists scrutinize them and all of the other photographs for any indication of moons. While the search will continue, so far, no picture has shown evidence of companions orbiting Ceres.

And yet we know that as of today, Ceres most certainly does have one. Its name is Dawn!

Dawn is 37,800 miles (60,800 kilometers) from Ceres, or 16 percent of the average distance between Earth and the moon. It is also 3.33 AU (310 million miles, or 498 million kilometers) from Earth, or 1,230 times as far as the moon and 3.36 times as far as the sun today. Radio signals, traveling at the universal limit of the speed of light, take 55 minutes to make the round trip.

Dr. Marc D. Rayman

6:00 a.m. PST March 6, 2015

› Read more entries from Marc Rayman's Dawn Journal

TAGS: DAWN, CERES, VESTA, DWARF PLANET, ORBIT INSERTION, SPACECRAFT, MISSION

Dawn Journal | February 25, 2015

Dawn's Approach Takes Shape as the Face of Ceres is Revealed

Dear Fine and Dawndy Readers,

The Dawn spacecraft is performing flawlessly as it conducts the first exploration of the first dwarf planet. Each new picture of Ceres reveals exciting and surprising new details about a fascinating and enigmatic orb that has been glimpsed only as a smudge of light for more than two centuries. And yet as that fuzzy little blob comes into sharper focus, it seems to grow only more perplexing.

Dawn is showing us exotic scenery on a world that dates back to the dawn of the solar system, more than 4.5 billion years ago. Craters large and small remind us that Ceres lives in the rough and tumble environment of the main asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter, and collectively they will help scientists develop a deeper understanding of the history and nature not only of Ceres itself but also of the solar system.

Even as we discover more about Ceres, some mysteries only deepen. It certainly does not require sophisticated scientific insight to be captivated by the bright spots. What are they? At this point, the clearest answer is that the answer is unknown. One of the great rewards of exploring the cosmos is uncovering new questions, and this one captures the imagination of everyone who gazes at the pictures sent back from deep space.

› Full image and caption

Other intriguing features newly visible on the unfamiliar landscape further assure us that there will be much more to see and to learn -- and probably much more to puzzle over -- when Dawn flies in closer and acquires new photographs and myriad other measurements. Over the course of this year, as the spacecraft spirals to lower and lower orbits, the view will continue to improve. In the lowest orbit, the pictures will display detail well over one hundred times finer than the RC2 pictures returned a few days ago (and shown below). Right now, however, Dawn is not getting closer to Ceres. On course and on schedule for entering orbit on March 6, Earth's robotic ambassador is slowly separating from its destination.

"Slowly" is the key. Dawn is in the vicinity of Ceres and is not leaving. The adventurer has traveled more than 900 million miles (1.5 billion kilometers) since departing from Vesta in 2012, devoting most of the time to using its advanced ion propulsion system to reshape its orbit around the sun to match Ceres' orbit. Now that their paths are so similar, the spacecraft is receding from the massive behemoth at the leisurely pace of about 35 mph (55 kilometers per hour), even as they race around the sun together at 38,700 mph (62,300 kilometers per hour). The probe is expertly flying an intricate course that would be the envy of any hotshot spaceship pilot. To reach its first observational orbit -- a circular path from pole to pole and back at an altitude of 8,400 miles (13,500 kilometers) -- Dawn is now taking advantage not only of ion propulsion but also the gravity of Ceres.

On Feb. 23, the spacecraft was at its closest to Ceres yet, only 24,000 miles (less than 39,000 kilometers), or one-tenth of the separation between Earth and the moon. Momentum will carry it farther away for a while, so as it performs the complex cosmic choreography, Dawn will not come this close to its permanent partner again for six weeks. Well before then, it will be taken firmly and forever into Ceres' gentle gravitational hold.

The photographs Dawn takes during this approach phase serve several purposes. Besides fueling the fires of curiosity that burn within everyone who looks to the night sky in wonder or who longs to share in the discoveries of celestial secrets, the images are vital to engineers and scientists as they prepare for the next phase of exploration.

› Full image and caption

› Full image and caption

The primary purpose of the pictures is for "optical navigation" (OpNav), to ensure the ship accurately sails to its planned orbital port. Dawn is the first spacecraft to fly into orbit around a massive solar system world that had not previously been visited by a spacecraft. Just as when it reached its first deep-space target, the fascinating protoplanet Vesta, mission controllers have to discover the nature of the destination as they proceed. They bootstrap their way in, measuring many characteristics with increasing accuracy as they go, including its location, its mass and the direction of its rotation axis.

Let's consider this last parameter. Think of a spinning ball. (If the ball is large enough, you could call it a planet.) It turns around an axis, and the two ends of the axis are the north and south poles. The precise direction of the axis is important for our mission because in each of the four observation orbits (previews of which were presented in February, May, June and August), the spacecraft needs to fly over the poles. Polar orbits ensure that as Dawn loops around, and Ceres rotates beneath it every nine hours, the explorer eventually will have the opportunity to see the entire surface. Therefore, the team needs to establish the location of the rotation axis to navigate to the desired orbit.

We can imagine extending the rotation axis far outside the ball, even all the way to the stars. Current residents of Earth, for example, know that their planet's north pole happens to point very close to a star appropriately named Polaris (or the North Star), part of an asterism known as the Little Dipper in the constellation Ursa Minor (the Little Bear). The south pole, of course, points in exactly the opposite direction, to the constellation Octans (the Octant), but is not aligned with any salient star.

With their measurements of how Ceres rotates, the team is zeroing in on the orientation of its poles. We now know that residents of (and, for that mater, visitors to) the northern hemisphere there would see the pole pointing toward an unremarkable region of the sky in Draco (the Dragon). Those in the southern hemisphere would note the pole pointing toward a similarly unimpressive part of Volans (the Flying Fish). (How appropriate it is that that pole is directed toward a constellation with that name will be known only after scientists advance their understanding of the possibility of a subsurface ocean at Ceres.)