Towering Infernos

|  |  |

| Image Composite | Visible Light Image | Eagle Nebula Comparison |

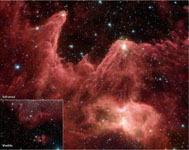

This majestic false-color image from NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope shows the "mountains" where stars are born. Dubbed "Mountains of Creation" by Spitzer scientists, these towering pillars of cool gas and dust are illuminated at their tips with light from warm embryonic stars.

The new infrared picture is reminiscent of Hubble's iconic visible-light image of the Eagle Nebula, which also features a star-forming region, or nebula, that is being sculpted into pillars by radiation and winds from hot, massive stars. The pillars in the Spitzer image are part of a region called W5, in the Cassiopeia constellation 7,000 light-years away and 50 light-years across. They are more than 10 times in the size of those in the Eagle Nebula (shown to scale here).

The Spitzer's view differs from Hubble's because infrared light penetrates dust, whereas visible light is blocked by it. In the Spitzer image, hundreds of forming stars (white/yellow) can seen for the first time inside the central pillar, and dozens inside the tall pillar to the left. Scientists believe these star clusters were triggered into existence by radiation and winds from an "initiator" star more than 10 times the mass of our Sun. This star is not pictured, but the finger-like pillars "point" toward its location above the image frame.

The Spitzer picture also reveals stars (blue) a bit older than the ones in the pillar tips in the evacuated areas between the clouds. Scientists believe these stars were born around the same time as the massive initiator star not pictured. A third group of young stars occupies the bright area below the central pillar. It is not known whether these stars formed in a related or separate event. Some of the blue dots are foreground stars that are not members of this nebula.

The red color in the Spitzer image represents organic molecules known as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. These building blocks of life are often found in star-forming clouds of gas and dust. Like small dust grains, they are heated by the light from the young stars, then emit energy in infrared wavelengths.

This image was taken by the infrared array camera on Spitzer. It is a 4-color composite of infrared light, showing emissions from wavelengths of 3.6 microns (blue), 4.5 microns (green), 5.8 microns (orange), and 8.0 microns (red).

The image composite compares an infrared image taken by NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope to a visible-light picture of the same region. While the infrared view, dubbed "Mountains of Creation," reveals towering pillars of dust aglow with the light of embryonic stars (white/yellow), the visible-light view shows dark, barely-visible pillars. The added detail in the Spitzer image reveals a dynamic region in the process of evolving and creating new stellar life.

Why do the pictures look so different? The answer has two parts. First, infrared light can travel through dust, while visible light is blocked by it. In this case, infrared light from the stars tucked inside the dusty pillars is escaping and being detected by Spitzer. Second, the dust making up the pillars has been warmed by stars and consequently glows in infrared light, where Spitzer can see it. This is a bit like seeing warm bodies at night with infrared goggles. In summary, Spitzer is both seeing, and seeing through, the dust.

The Spitzer image was taken by the infrared array camera on Spitzer. It is a 4-color composite of infrared light, showing emissions from wavelengths of 3.6 microns (blue), 4.5 microns (green), 5.8 microns (orange), and 8.0 microns (red).

The visible-light image is from California Institute of Technology's Digitized Sky Survey.