Meet JPL Interns | August 16, 2018

Getting New Perspectives on a Potential Ocean World

There’s no telling what the first spacecraft to land on Jupiter’s ice-covered moon Europa could encounter – but this summer, JPL intern Maya Yanez is trying to find out. As part of a team designing the potential Europa Lander, a mission concept that would explore the Jovian moon to search for biosignatures of past or present life, Yanez is combing through images, models, analogs, anything she can find to characterize a spot that’s “less than a quarter of a pixel on the highest-resolution image we have of Europa.” We caught up with Yanez, an undergraduate student at the University of Colorado at Boulder, to find out what inspired her to get involved in space exploration and ask about her career ambition to discover alien life.

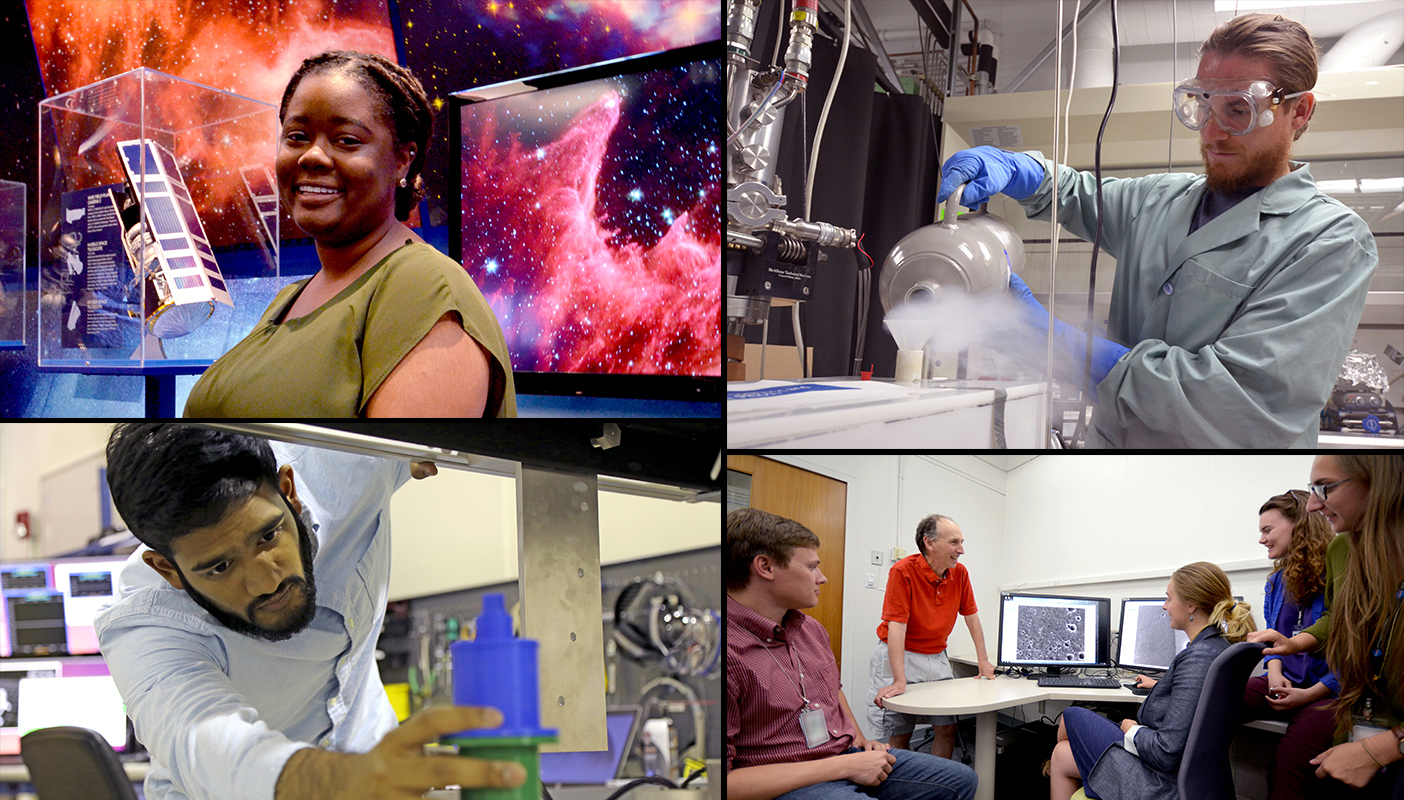

Meet JPL Interns

Read stories from interns pushing the boundaries of space exploration and science at the leading center for robotic exploration of the solar system.

What are you working on at JPL?

I'm working on what may be a robot that we would land on Europa's icy surface. Europa is a moon of Jupiter that has this thick ice shell that we estimate is 25 kilometers [15.5 miles] thick, and there’s evidence that underneath that is a huge global ocean. If we're going to find life beyond Earth, it's probably going to be wherever there's water. So this mission concept would be to put a lander on Europa to try to figure out if there are signs of life there. I’m looking at an area on Europa about two square meters [about 7 feet] and about a meter [3 feet] deep. For perspective, we've only explored a few kilometers into our own Earth's surface. What I'm doing is trying to figure out what we might expect is going on in that little tiny area on Europa. What light is interacting with it, what processes might be going on, what little micrometeorites are hitting the surface, what's the ice block distribution? I'm looking at places like Mars, the Moon and Earth to try to put constraints and understanding around what types of variation we might see on Europa and what might be going on underneath the surface.

What's an average day like for you?

A lot of it is looking up papers and trying to get an idea of what information exists about Europa. My first couple of weeks here, I read this thing that we call the "Big Europa Book.” It's a 700-page textbook that covers basically all of our knowledge of Europa.

One of the other things that I've been working on is a geologic map, trying to look at what geologic variation exists in a couple of meters on Europa because we don't know. It's kind of crazy to think that when Viking [the first Mars lander] landed, we had no clue what another surface would look like except for the Moon. We had no idea. And then we got those first amazing images and it looked kind of like Earth, except Europa probably won't look like Earth because it's not rock; it's all ice. So even though we're trying, we still have nothing to compare it to.

If it gets selected as an official mission, a Europa lander would come after NASA’s Europa Clipper spacecraft. How might data from Europa Clipper contribute to what you're working on now?

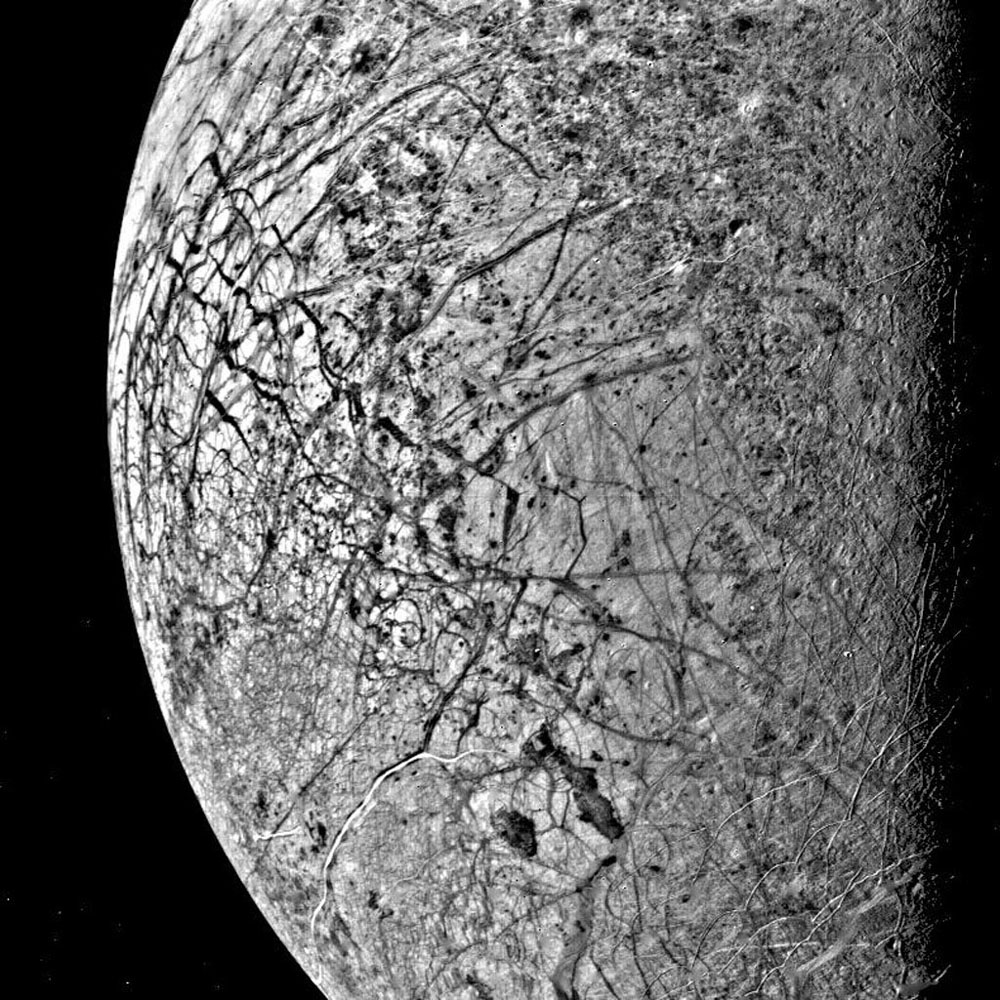

This image of Jupiter's moon Europa was acquired by NASA's Voyager 2 spacecraft on July 9, 1979, from a distance of about 240,000 kilometers (150,600 miles). Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech | › Full image and caption

This image is the most detailed view of Europa, obtained by NASA's Galileo mission on Dec. 16, 1997, at a distance of 560 kilometers (335 miles) from the surface. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech | › Full image and caption

Europa Clipper could be really beneficial in that it's going to do more than 40 flybys where it goes around Europa in a bunch of different ways and at different proximities. It’s going to curve into the moon’s atmosphere and get really close to the surface, about 25 kilometers [15.5 miles] close to the surface. Right now, some of the best data we have is from hundreds of kilometers away, so the images Europa Clipper will take will be pretty nicely resolved. If you look at the current highest resolution image of Europa as compared to one from Voyager [which flew by Jupiter and its moons in 1979], the amount of detail that changes, the amount of cracks and complexity you can see on the surface is huge. So having more images like that can be really beneficial to figure out where we can land and where we should land.

Before this project, you spent a summer at JPL studying the chemistry of icy worlds, such as Pluto. What’s it been like working on such different projects and getting experience in fields outside your major, like chemistry and geology?

[Laughs] Yeah, one day I'll get back to astronomy. That's one of the things I love about JPL. Overall, I'd say what I want to do is astrobiology because I want to find life in the solar system. I mean, everyone does. It would be really cool to find out that there are aliens. But one of the great things about astrobiology is it takes chemistry, physics, geology, astronomy and all of these different sciences that you don't always mix together. And that's kind of why I like JPL. So much of the work involves an interdisciplinary approach.

What's the most JPL- or NASA-unique experience you've had so far?

I have one from last summer and one from this summer.

I really want to find life out in space. I'm curious about bacteria and microbes and how they react in space, but it's not something I've ever really done work in. A couple of weeks ago, I got to see astronaut Kathleen Rubins give a talk, meet her afterward and take a picture with her. She was the first person to sequence DNA in space. I would have never met someone like that if it weren’t for my internship at JPL. I wouldn't have been able to go up to her and say, “This is really cool! I'd love to talk to you more and get your email” – and get an astronaut's email! Who would ever expect that?

And then last year, I had something happen that was completely unexpected. I was sitting alone in the lab, running an experiment and, throughout the summer, we had a couple of different tours come through. A scientist asked if he could bring in a tour. It was two high-school-age kids and, presumably, their moms. I showed them around and explained what my experiment was doing. It was great. It was a really good time. They left and a couple hours later, Mike Malaska, the scientist who was leading the tour, came back and said, “Thank you so much for doing that tour. Do you know the story of that one? I said no. He said, “Well the boy, he has cancer. This is his Make-a-Wish.” His Make-a-Wish was to tour JPL. I had never felt so grateful to be given the opportunity that I was given, to realize that someone’s wish before they may or may not die is to visit the place that I'm lucky enough to intern at. It was a very touching moment. It really made me happy to be at JPL.

What was your own personal inspiration for going into astronomy?

I was the nerdy kid. I had a telescope, but I also had a microscope. So it was destined. But in middle school, I started to get this emphasis on life sciences. I'd always really liked biology so I sort of clung to it. We never really talked about space, so I just kind of forgot about it. But my senior year, I took this really cool class in astrobiology taught by an amazing teacher, who I still talk to. After the first week in her class, I was like, I have to do this. At the end of the academic year, that same teacher took me to JPL and gave me a private tour with some of the other scientists. I actually met Morgan Cable, the mentor I worked with last summer and this summer, on that tour. It was definitely a combination of being in this really great class and having that perspective change, realizing that we’ve learned a lot about life on our own planet, but there's so much to learn about finding it elsewhere.

Did you know about JPL before that?

No. I'm the first generation in my family to go to college, so I'm the one who teaches science to everyone else. I didn't even think science was a career because, when you're a kid, you don't often interact with a lot with scientists. So I didn't realize what JPL was or how cool it was until that tour put everything into perspective. I wasn't a space kid, but I found my own path, and it worked.

Yanez hosted a takeover of the @NASAJPL_Edu Twitter account during the NASA Internships Town Hall with Administrator Jim Bridenstine. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Kim Orr | + Expand image

For National Intern Day on July 26, NASA held a special town hall for interns with Administrator Jim Bridenstine. Your question about how the agency prioritizes the search for extraterrestrial life was selected as a finalist to appear during the broadcast. What made you want to ask that particular question?

So it was a little self-serving [laughs]. Part of it is that it’s central to my career path, but I also want to run for office one day at some level, and I think it's important that there's this collaboration between science and politics. Without it, science doesn't get funded and politicians aren’t as well informed.

How do you feel you're contributing to NASA/JPL missions and science?

What I'm doing requires a lot of reading and putting things together and knowing rocks and putting scales into perspective, so it's not particularly specialized work. But the end goal of my project will be a table that says here's what processes are happening on Europa, here's what depth they govern and here's what it means if biosignatures are caught in these processes. I'm also going to be remaking an old graphic, including more information and trying to better synthesize everything that we know about Europa. Those two products will continue to be used by anyone who’s thinking about landing on Europa, for anyone who’s thinking about what surface processes govern Europa. Those two products that I'm producing are going to be the best summaries that we have of what's going on there.

OK, so now for the fun question: If you could travel to any place in space, where would you go and what would you do there?

Europa. Obviously [laughs]. Or [Saturn’s moon] Titan. Titan is pretty cool, but it scares me a little bit because there's definitely no oxygen. There's not a lot of oxygen on Europa, but what's there is oxygen. I would probably go to Europa and find some way to get through those 25 kilometers of ice, hit that ocean and see what's going on.

Explore JPL’s summer and year-round internship programs and apply at: https://www.jpl.nasa.gov/edu/intern

The laboratory’s STEM internship and fellowship programs are managed by the JPL Education Office. Extending the NASA Office of Education’s reach, JPL Education seeks to create the next generation of scientists, engineers, technologists and space explorers by supporting educators and bringing the excitement of NASA missions and science to learners of all ages.

TAGS: Women in STEM, Internships, Interns, College, Students, STEM, Science, Engineering, Europa, Europa Clipper, Europa Lander, Ocean Worlds, Hispanic Heritage Month

Meet JPL Interns | July 24, 2018

Diving Deep on the Science of Alien Oceans

Kathy Vega went from teaching STEM to doing it first-hand. Now, as an intern at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, she's building an experiment to simulate ocean worlds. We recently caught up with Vega, a University of Colorado at Boulder engineering physics major, to find out what inspired her to switch careers and how her project is furthering the search for life beyond Earth.

What are you working on at JPL?

In our solar system, there are these icy worlds. Most of them are moons around large gas planets. For example, Europa is an icy moon that orbits Jupiter. There's also Titan and Enceladus orbiting Saturn. From prior missions, such as Galileo and Cassini, we've been able to see that these moons are covered with ice and most likely harbor oceans below that ice, which makes us wonder if these places are habitable for life. My project is supporting the setup of an experiment to simulate possible ocean compositions that would exist on these worlds under different temperatures and different pressures. Working in collaboration with J. Michael Brown’s group at the University of Washington in Seattle, this experiment is helping create a library of measurements that have not been collected before. Eventually, it may help us prepare for the development of landers to go to Europa, Enceladus and Titan and collect seismic measurements that we can compare to our simulated ones.

Meet JPL Interns

Read stories from interns pushing the boundaries of space exploration and science at the leading center for robotic exploration of the solar system.

What's a typical day like for you?

Right now, I'm in experiment-design mode. I've been ordering parts for the experiment and speaking with engineering companies. This experiment is already being run at UW in Seattle, but we're attempting to run it at colder temperatures to do a wider range of simulations, which haven’t been done before and will be particularly relevant to Jupiter’s moon Ganymede and Saturn’s moon Titan. I've been working with another intern, and we've been meeting with cryogenic specialists and experiment-design specialists at JPL to design a way to make our current experiment reach colder temperatures.

I also run a lot of simulations with Matlab software. There's a model that my principal investigator developed called Planet Profile that allows the user to input different temperature ranges and composition profiles for a planetary body. It then outputs the density and sound-velocity measurements that we would expect in that environment.

What's the most JPL- or NASA-unique experience you've had so far?

The Europa Clipper mission, [which will orbit Jupiter’s moon Europa to learn more about it and prepare for a future lander], is in development right now. A major planning meeting for the mission was held at JPL, and I got to sit in and watch these world-renowned scientists, who I think are like rock stars, talk science. There were all of these people having an open-forum discussion and, gosh, it was so cool. I felt like I was there with the people who are planning the future.

You already have a degree in political science. What made you want to go back to school for STEM?

When I was in high school, I was in Mathletes, but I was also in Mock Trial. I took AP physics, AP chemistry, AP calculus, but also AP civics and AP history. I remember in my junior year, I thought, I love math. Maybe I could be an astronaut one day. Space is so cool. Then AP physics happened. I didn't fail or anything, but after that, I just felt like maybe it's not for me.

Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Kim Orr | + Expand image

There were also a lot of critical things happening with politics around that time. Immigration was a really hot topic and walkouts were happening at L.A high schools. My family is from El Salvador, and I'm a first-generation college student, so I felt very motivated to study political science and be involved in issues that were happening first-hand in the world and affected my family and people I knew. So I went to Berkeley and got a degree in political science.

After that, I really wanted to get involved with service and just make a difference in the world, so I joined Teach for America. I taught math and I started a robotics club. It was through the robotics club and teaching my students about space and engineering that I really got excited again. I started pressing my siblings and my cousins to go into science. And one day, one of my cousins said, "If space is so cool, Kathy, why aren't you studying it?" I realized, yeah, what happened to that? I really loved that. So I decided to take classes at a local community college and did well. And now I’m at the University of Colorado at Boulder getting a second degree in engineering physics.

Do you ever feel pulled back in the direction of politics?

No [laughs]. Politics is a messy ordeal. I do my part as a citizen, but I like to think that thinking toward the future in science is where my efforts are best used right now.

How do you feel your background in political science has served you in engineering?

Going into engineering and science, I was very conscious of the fact that women and especially women of color are underrepresented in these fields. I think that having the background in political science, having the experiences working with communities gives me the ability to have thoughtful conversations with people about diversity.

How do you think you're contributing to NASA/JPL missions and science?

With this experiment, I've been able to leverage my creative side. I feel like I'm laying the foundation for these missions to explore other moons and worlds.

If you could travel to any place in space, where would you go and what would you do there?

There’s a star called Vega, and it might have its own planetary system. It's so far that we have no idea what's in that potential system or if there could be terrestrial planets. I'd want to explore that.

Explore JPL’s summer and year-round internship programs and apply at: https://www.jpl.nasa.gov/edu/intern

The laboratory’s STEM internship and fellowship programs are managed by the JPL Education Office. Extending the NASA Office of Education’s reach, JPL Education seeks to create the next generation of scientists, engineers, technologists and space explorers by supporting educators and bringing the excitement of NASA missions and science to learners of all ages.

TAGS: Women in STEM, Interns, Internships, College, Higher Education, STEM, Europa, Europa Clipper, Europa Lander, Science, Ocean Worlds, Hispanic Heritage Month, Women at NASA